1949 Twelve countries sign the North Atlantic Treaty on 4 April 1949 in Washington, D. C. and bring the Alliance to life. ()

A Glance at NATO’s History

The establishment of NATO was primarily influenced by the United States’ Anglo-Saxon ties and the need for strategic cooperation with Europe. (Roberts P. , 2009) While the US initially operated under the principles of the Monroe Doctrine (Moore, 1896) until the completion of its founding processes, the global conjuncture following the First World War revealed that this approach was no longer viable.

The decline of the United Kingdom and France in mainland Europe, the ineffectiveness of the post-war League of Nations, and the reactions of the defeated states to the treaties made the emergence of the Second World War almost inevitable. Germany’s qualified human resources, whose economy had been turned upside down, enabled it to recover quickly and have an enormous war industry. National Socialism and Hitler’s expansionist policy, which emerged from manipulating the sense of defeat in German society, ultimately led to the Second World War.

Despite the persistent demands of the United Kingdom, the United States initially stayed out of the war but became involved after the Pearl Harbor raid in 1941. The conferences towards the end of the war indicated the ideological polarization of the post-war period. When it became clear that communist Russia, which had reached Berlin with the Red Army, was a new threat, a new division in Europe was shaped after the Potsdam Conference. This conference divided Europe into Eastern Europe under the power of Russia and Western Europe under the control of the Western blog led by the USA (Roberts G. , 2007).

The balance of power that began with the US entry into the war and emerged in the aftermath of the war necessitated the transition of the US from the Monroe Doctrine to the Truman Doctrine. The Marshall Plan, which was put forward with the Truman Doctrine, aimed for the post-war European states to recover from the war’s effects and develop economically. (J. Bradford De Long, 1991) In this context, the European Coal and Steel Union was established to prevent Germany, which was defeated in the war, from another conflict with Western Europe, and this union became today’s European Union (EU). On the other hand, NATO was established to protect the West and Western values against the threat posed by Soviet Russia.

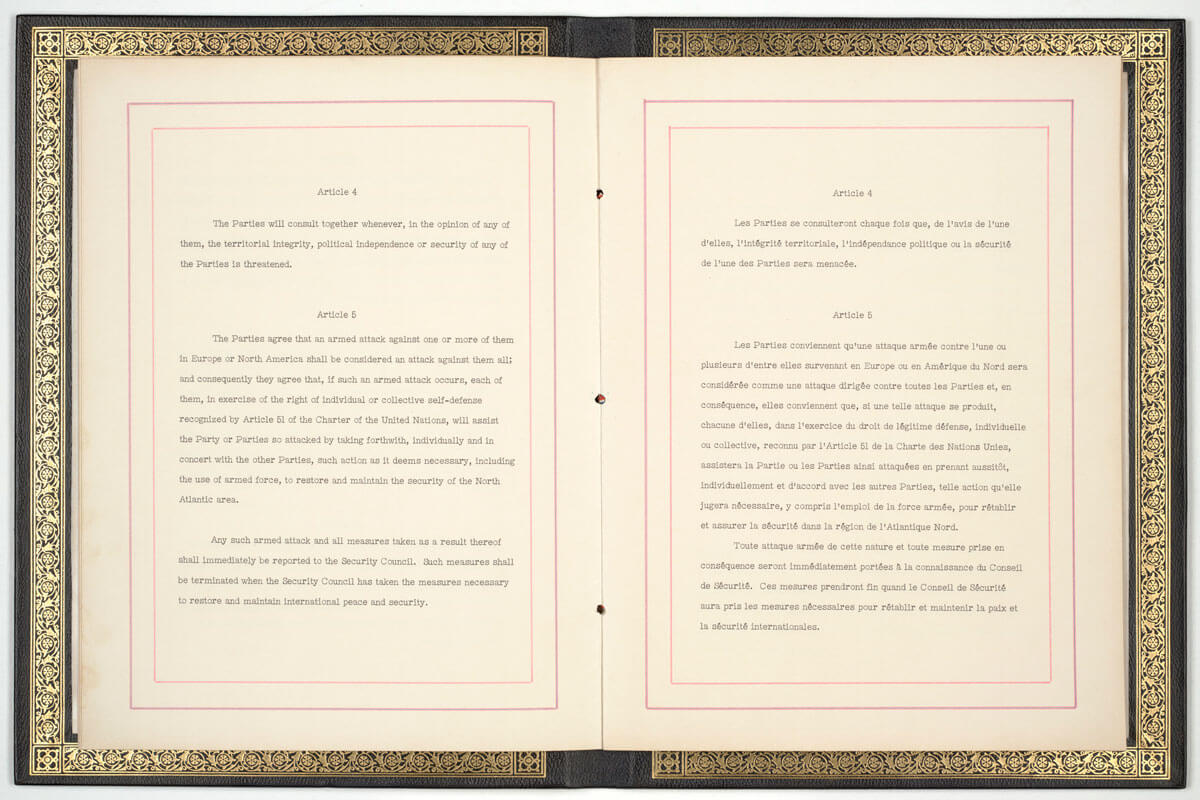

Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty will be on display at the National Archives in Washington, DC, through April 2, 2019, in honor of the 70th anniversary of the document. (National Archives: General Records of the United States Government) ()

NATO was established on April 4, 1949, with the Washington Treaty signed between the 12 founding states. (NATO, North Atlantic Treaty, 2024) The Treaty regulates the defense cooperation of Europe and North America on both sides of the Atlantic. The Treaty consists of 14 apparent and superficial articles. The military dimension of the Treaty is regulated by Article 5 of the Washington Treaty, the collective defense article. Politically, as stated on its official website, NATO is committed to “promoting democratic values and enabling members to consult and cooperate on defense and security matters to solve problems, build trust, and prevent conflict in the long term.” NATO’s decision-making mechanism is based on consensus decision-making by member states. (NATO, North Atlantic Treaty, 2024)

When considering NATO’s establishment and development, it is important to take into account the post-establishment Cold War period, the dissolution of the USSR and NATO’s expansion, the September 11 attacks and the paradigm shift, and finally, the new threat environment that emerged with Russia’s aggression against Ukraine.

The most prominent feature of the Cold War era was deterrence. Under the strategic doctrine of the so-called “Great Retaliation”, nuclear weapons deterrence deterred both sides from taking risks, allowing alliance members to focus their energies on economic growth rather than building large conventional armies. Following the Korean War, Turkey and Greece became members of NATO in 1952 and Germany in 1955. At the same time that Germany joined NATO, the USSR formed the Warsaw Pact, with the states under its control. (Sayle, 2019)

One of the most crucial turning points of the Cold War period was the Cuban Missile Crisis. However, Kennedy and Khrushchev’s efforts to defuse the crisis led to the beginning of the so-called “détente” period. In this period, relations between the USA and the USSR improved, marked by arms control agreements, improved diplomatic relations, cultural exchanges, economic cooperation, and reduced proxy conflicts. Though this relatively calm period ended with the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty signed between the US and the USSR in 1987 was seen as the first significant sign of a new era.

Although there are different views on what led to the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact, the most crucial factor was the loss of the Soviet Union’s ability to sustain the competition. The resulting Glasnost and Perestroika policies initiated a period of upheaval, starting with the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and culminating in the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact.

When the costs of the defense systems countries build to protect their assets spiral out of control, it may threaten their future. Perhaps the most crucial evidence of this is the disintegration of the Soviet Union. The repressive policies pursued in the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc seem to have postponed the disintegration. However, it should be noted that this cost is also one of the most critical obstacles to such irrational, unsustainable defense policies of societies with democratic values.

The September 11 attacks, which occurred while NATO was debating its new mission after being left unchallenged for some time, led to a comprehensive paradigm shift. Non-state actors, previously not considered a significant threat, were included in threat perceptions, and a new approach to eliminating the threat at its source, called preemptive strike, was adopted. This new approach has also led to non-state actors increasingly becoming an international strategy instrument and proxy wars’ emergence. In addition to conventional threats/means, hybrid threats/means with asymmetric effects have been widely used, and the military operational environment has gradually shifted from traditional operations to urban and asymmetric/hybrid warfare.

The era that began with the collapse of the Soviet Union was also a period of NATO’s expansion, with former Warsaw Pact members and other Eastern European countries joining NATO. Between 1999 and 2009, 12 more countries joined NATO. By 2022, when the Ukraine-Russia War started, the number of members had reached 30. This expansion brought the post-Soviet Union Russian Federation closer and closer to NATO’s borders.

Return of Russia

The Russian Federation, which under Yeltsin focused on its internal affairs and accepted the status quo, started to pursue an increasingly active policy under Putin. When the search for pro-Western, democratic regimes that emerged in other Eastern European states also manifested itself in Georgia and Ukraine, Russia’s response was much more aggressive.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia employed unconventional methods to ensure that governments close to Russia remained in power in the countries of the former Soviet Union, leading to extraordinary control changes in many countries. Georgia’s rapprochement with the West led to similar political instability, and ultimately, with Saakashvili coming to power, Russia destroyed Georgia’s territorial integrity through direct military intervention in 2008. This war resulted in Russia achieving its goals due to its severe power superiority, which holds important lessons for Russia, NATO, and the Western world in many respects.

In the Georgian war, Russia had the opportunity to measure its combat readiness with unprecedented clarity and make significant changes in the structure of its Armed Forces after the war. On the other hand, this war enabled Russia to assess the Western world’s likely reaction to a similar situation in its hinterland and its implications for possible action. This war provided Russia with essential insights and served as a learning opportunity for the war in Ukraine, militarily in the form of a combat readiness exercise and politically in the form of an international public opinion poll. Subsequently, from the annexation of Crimea to the invasion of Ukraine, it is evident that Russia applied the lessons learned from the Georgian war effectively. (Beehner, Collins, Ferenzi, Person, & Brantly, 2018)

The Western world and NATO have seen that providing support for targeted countries like Georgia, which have significant military and geographical disadvantages, will be insufficient if direct military intervention is not considered. From a political point of view, it has been seen that Russia will not tolerate pro-Western/NATO policies in the regions it regards as its backyard and will resort to any means, including territorial occupation, if necessary, to prevent it.

Ukraine-Russia relations have been very distinct from those of other Soviet Union countries. Ukraine, which has played a crucial role in Russia’s oil and natural gas policy, has always held a privileged position for Russia regarding the development of the defense industry and economic investments, including in nuclear energy. The transfer of Crimea, one of the most significant naval centers for Russia, to the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic in 1954, and the failure or inability of the Russian administration of the period to prevent Crimea, which was autonomous in 1991 during the dissolution of the Soviet Union, from joining Ukraine in 1992, triggered a series of events that began with the Orange Revolution, continued with the annexation of Crimea, and ultimately led to the occupation of Ukraine. However, it should be noted that the root of the problem is not limited to Crimea but is also a result of Russia’s defense strategy against NATO’s expansion. (Henrikson, 2022)

In this war, Russia employed a strategy similar to the one used in Georgia, its ability to sustain a larger-scale operation for a more extended period by acquiring new capabilities through its military experience. Russia’s ability to continue the war, despite the sanctions limiting its national power elements and the support provided to Ukraine, albeit of questionable adequacy, depends to a significant extent on its oil and natural gas resources, as well as the advantages of an authoritarian regime and the ability to risk losses that an average democratic government cannot afford. Putin’s threatening statements from the very beginning of this period were partly motivated by the idea that NATO and the Western world would be unable to take the losses he was willing to take.

As for Russia, the Soviet Union’s unsustainable defense expenditures based on Soviet Russia’s threat assessment led to the political end of the union. Conversely, Putin’s failure to take the minimum necessary steps to maintain the prosperity and peace enjoyed by the European states might embolden him to expand the campaign, potentially plunging Europe into war and instability.

So, what is the purpose of NATO?

In addition to its military and political effects, the war in Ukraine has also led to a tragedy with civilian casualties and the displacement of millions of people who have become refugees. NATO’s support for Ukraine and its strategy to limit Russia’s ability to continue the war must take into account the effects of this humanitarian tragedy.

The United States’ leading role, which has existed since NATO’s inception, has meant that the alliance has borne a significant economic and military burden. While this initially enabled the development of European states, maintaining peace in the current threat environment requires a greater contribution from all member states, especially the United Kingdom and European Union countries with advanced economies.

The inadequacy of defense spending, which has come under public scrutiny again with the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, shows that even the United Kingdom, Germany, France, and Italy cannot sustain a conventional military operation in a potential crisis. This is further highlighted by the United Kingdom’s Strategic Security and Defense Document (MOD, 2015), published in 2015, specializing in the defense and security relationship with the United States for its national defense system. The document suggests that there has not been a significant change in the strategic balance of power on the European continent since the Second World War.

It would be a grave oversight to view the points in Article 48 of NATO’s 2022 Strategic Concept as simply a 2% threshold (NATO, 2022). In this context, it is vital that NATO, which is celebrating its 75th anniversary, not only maintains and improves its current deterrence capabilities but also re-examines the ability of all member states to sustain a possible conventional operation and develop realistic defense policies.

On the other hand, political, economic, and military support should be provided to economically inadequate member states to facilitate their financial and military development. In this context, it is essential to promote transparency, adherence to democratic values, universal rules of law, and an understanding of economic requirements to ensure that military and financial aid have a lasting impact.

Last but not least, NATO’s founding principles and adherence to them should always be indispensable and shed light on NATO’s vision, mission, organizational goals, and strategies. Considering the significant potential damage to NATO’s common security strategy caused by domestic political dynamics influenced by rising popular nationalist movements, it is crucial to uphold adherence to NATO’s founding principles in every aspect.

References

Beehner, L., Collins, L., Ferenzi, S., Person, R., & Brantly, A. (2018). Analyzing the Russian Way of War Evidence from the 2008 Conflict with Georgia. West Point Modern War Institute.

Henrikson, A. K. (2022). The Trauma of Territorial Break-up: The Russia-Ukraine Conflict and Its International Management—Geopolitical Strategy and Diplomatic Therapy. Geopolítica(s) Revista de estudios sobre espacio y poder, 11-36.

J. Bradford De Long, B. E. (1991). THE MARSHALL PLAN: HISTORY’S MOST SUCCESSFUL. Cambridge: NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH.

MOD, U. (2015). National Security Strategy and Strategic Defence and Security Review 2015, A Secure and Prosperous United Kingdom. London: UK Government.

Moore, J. B. (1896, March). The Monroe Doctrine. Political Science Quarterly, pp. 1-29. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/2139599

NATO. (2022, June 29). https://www.nato.int/. Retrieved from https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/2022/6/pdf/290622-strategic-concept.pdf: https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/2022/6/pdf/290622-strategic-concept.pdf

NATO. (2024, April 04). North Atlantic Treaty. Retrieved from https://www.nato.int/: https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/history_pdf/20161122_E1-founding-treaty-original-tre.pdf

Roberts, G. (2007). Stalin at the Tehran, Yalta, and Potsdam Conferences. Journal of Cold War Studies, 6-40.

Roberts, P. (2009, June 2). The transatlantic American foreign policy elite: its evolution in. Journal of Transatlantic Studies, pp. 163-183.

Sayle, T. A. (2019). Enduring Alliance: A History of NATO and the Postwar Global Order. London: Cornell University Press Ithaca and London.

As a graduate of the U.S. Army War College and a former senior civil servant, Mr. Umit Kurt is dedicated to advancing the field of international relations as a Ph.D. researcher at UCLouvain in international relations in Belgium.

His research delves into the dynamics of International Institutions with their diverse members, the ethics of reconciliation, the complexities of migration, and the overarching governance of digital ecosystems.

With a career that spans over two decades, he has been at the forefront of leading and contributing to task forces in various capacities, including NATO Peace Operations and strategic NATO Headquarters.

Mr Kurt’s professional journey has been enriched by a Master of Business Administration. His expertise in Global Governance for Digital Ecosystems was honed through a consultancy role at PA Europe-Belgium, a prominent multinational public affairs firm.