After the September 11 attacks, Special Operations Forces (SOF) use and importance have been increased dramatically. How to deploy SOF has become a heavily debated topic between academics and the military. This article examines the strategic utility of special operations forces as a policy tool for Homeland Security and Defense. Moreover, which type of missions and roles provide strategic value for national security. This article presents a theoretical and conceptual overview of special operations, strategic utility, and SOF roles and missions to provide a common understanding. The results were reached that SOF was not used in accordance with its capabilities and limitations, its weaknesses were not taken into account, and adequate strategic utility was not achieved.

I. Introduction

Today we see a bewildering diversity of separatist wars, ethnic and religious violence, coups d’état, border disputes, civil upheavals, and terrorist attacks, pushing waves of poverty-stricken, war-ridden immigrants (and hordes of drug traffickers as well) across national boundaries. In the increasingly wired global economy, many of these seemingly small conflicts trigger strong secondary effects in surrounding (and even distant) countries. Thus a “many small wars” scenario is compelling military planners in many armies to look afresh at what they call “special operations” or “special forces”—the niche warriors of tomorrow.[1] Alvin and Heidi Toffler

During the twentieth century, the nature of war was mainly built on the air-land battle doctrine. Although there had been some changes in military doctrines, the nature of the war remained the same until the end of the Cold War. With the end of the Cold War, the security environment and the combat area have changed. Irregular threats have replaced regular threats. Terrorism and small wars have been the most pressing issues of the United States. So SOF has become the most needed and deployed military unit. With its increasing importance, how SOF should be employed is also heavily debated.

After the September 11 attack, SOF was primarily used in direct-action (DA) missions to support conventional forces (CF).[2] The usage of SOF with conventional forces on direct actions was supported. Institutional constraints, leadership shortfalls, and poor understanding of SOF capabilities have led to the misuse of SOF as a strategic asset to combat irregular threats in complex and unstable environments.[3] SOF must primarily operate independently or as a supported organization to counter unconventional threats both directly and indirectly.[4] This arrangement will unleash the strategic potential of special operations (SO). Furthermore, the indirect role—operating by, with, and through an indigenous population—would better serve the Department of Defense (DoD) and SOCOM, and more importantly, strategy.

Having written substantially about SOF, Colin Gray characterizes their strategic utility as providing economy of force, expansion of choice, innovation, morale, showcasing of competence, reassurance to a domestic audience or ally, the humiliation of an enemy, control over escalation, and shaping of the future. According to Gray, the economy of force and expansion of choice are the most important of SOF’s strategic capabilities. The focus of this article will include cases that address the strategic utility of special operations forces.

There is general agreement that SOF’s potential strategic utility has increased in the last two decades. However, the focus of debate today is about the utilization of SOF to achieve a more significant strategic effect. There are two basic approaches. Some claim that the role of SOF should be limited to military operations of a unique nature. Therefore, the deployment of SOF as a principal element would be a mistake.[5] According to Kiras, “strategic effects are generated when SOF operate in conjunction with conventional forces’ campaigns of attrition, and not in the conduct of isolated raids.”

On the other hand, some “see the role of SOF as more expansive, a force that can be used to win the hearts and minds of the local population, a social-worker role in addition to military support.”[6] According to this approach, SOF would serve as a force multiplier for proxy forces and must be deployed as a leading force.[7]

World War II necessitated the development and employment of special units. It is generally accepted that the importance of SOF has increased in the last two decades due to the current security environment. The optimization of these specially deployed forces has long been debated among academics, decision-makers, and even within the SOF community. The literature on SOF consists mainly of battle narratives, unit campaign histories, and biographies. Some studies offer historical cases of SO.[8] Other studies examine the cultural differences between SOF and conventional forces.[9] Others discuss factors in the success and failure of SO.[10] Although many studies about SOF exist, research concerning the strategic value of SOF is limited. This article attempts to expand the discourse. First, it focuses on the concept of strategic utility. Initially, it defines SO, SOF, SOCOM, and the strategic environment to provide a common understanding of this issue. Next, the concept of strategic utility and its conditions is discussed. Second, it discusses SOF’s direct and indirect roles, missions, and where they operate, whether independently of conventional forces or in support of conventional forces. This chapter provides the advantages and disadvantages of each role and its potential strategic utility. Finally, the article concludes with some recommendations to deploy SOF more appropriately.

II. The Strategic Utility of Special Operations Forces

The increased role of special operation forces (SOF) in the current security environment has complicated the debate over appropriate SOF roles and missions. A lack of understanding of the best employment of SOF, and more specifically, how to achieve its optimal strategic utility continues. The problem may lie in the broad definition of SO, coupled with SO’s perceived narrow understanding both within DoD and beyond. Achieving optimal strategic utility requires a shared understanding of SO among policymakers and military leaders.

A. Special Operations (SO)

The literature provides many definitions of Special Operations and Special Operations Forces to address theories and concepts.[11] Currently, the Congressional Research Service (CRS) Report defines special operations as

…military operations requiring unique modes of employment, tactical techniques, equipment, and training. These operations are often conducted in hostile, denied, or politically sensitive environments and are characterized by one or more of the following elements: time sensitive, clandestine, low visibility, conducted with and/or through indigenous forces, requiring regional expertise, and/or a high degree of risk.[12]

According to Colin Gray, special operations are operations that regular forces cannot perform. “To restate the point from a different perspective, special operations lie beyond the bounds of routine tasks in war.”[13] In addition, he points out that the “boundary line between special operations and regular warfare is not always clear.”[14] Although Gray limits his discussion to special operations in war, special operations can also be conducted in the time of peace.

James Kiras claims that strategic effects are generated when SOF operates in conjunction with conventional forces’ campaigns of attrition and not in isolated raids. His book, Special Operations and Strategy is based on the concept of strategic paralysis and attrition. He defines special operations as

unconventional actions against enemy vulnerabilities in a sustained campaign, undertaken by specially designated units, to enable conventional operations and/or resolve economically, politico-military problems at the operational or strategic level that are difficult or impossible to accomplish with conventional forces alone.[15]

This definition limits special operations for enabling conventional operations. However, it is obvious that special operations can be conducted independently and have wide-ranging effects. Rescuing hostages from terrorists or executing a raid for political effect are well-known examples.

William H. McRaven describes a special operation as follows “a special operation is conducted by forces specially trained, equipped, and supported for a specific target whose destruction, elimination, or rescue (in the case of hostages), is a political or military imperative.”[16] The concept of “relative superiority” and the six principles of special operations—simplicity, security, repetition, surprise, speed, and purpose—are the basis of his book. Given his definition and eight case studies, he limits the debate to direct-action missions. Therefore, his book does not include the full scope of special operations.

Lucien S. Vandenbroucke has focused on the misuse of SOF in his work Perilous Options. According to Vandenbroucke, faulty intelligence, poor interagency and interservice cooperation and coordination, inadequate information and advice provided to decision-makers, wishful thinking, and overcontrol of mission execution are the main problems in strategic special operations.[17] In addition, he defines SO as: “[secret military or paramilitary strikes, approved at the highest level of the U.S. government after detailed review] such strikes can be called strategic special operations. Executed in limited time and with limited resources, they seek to resolve through the sudden, swift, and irregular application of force major problems of U.S. foreign policy.”[18] This definition excludes unconventional warfare and non-kinetic forces such as civil affairs and MISO.

Maurice Tugwell and David Charters offer one of the most useful special-operations definitions: “small-scale, clandestine, covert or overt operations of an unorthodox and frequently high-risk nature, undertaken to achieve significant political or military objectives in support of the foreign policy.”[19] Although the objectives’ connection to foreign policy is vague, this definition captures special operations’ key aspects.

The preceding discussion confirms that no common understanding and definition of special operations exists. Therefore, it is first necessary to discuss the concept of strategic utility and its relationship to special operations. This article proceeds from the following assumptions. First, special operations can be conducted in all environments, from peace through war. Second, they can achieve military objectives and diplomatic, informational, and economic objectives of all national power elements.[20] Third, special operations can be conducted either in conjunction with conventional forces campaigns or independently to counter irregular threats. Finally, special operations consist of direct and indirect missions–not merely one type of mission.

B. Special Operations Forces (SOF) and SOCOM

The DoD defines SOF as “Active Component and Reserve Component (RC) forces of the Services specifically organized, trained, and equipped to conduct and support SO.”[21] In other words, SOF conducts special operations.

SOCOM is responsible for SOF. Operation Eagle Claw’s failure, the attempt to rescue hostages from the U.S Embassy in Iran in 1980, led to SOCOM’s establishment. SOCOM deploys and supports SOF to conduct CF operations, provide coordination among all SOF elements, and achieve more efficient command-and-control (C2).[22] SOCOM is unique since it is responsible for both the conduct of military operations and Service responsibilities such as training, equipping, and recruiting.

SOCOM consists of the following components: Army Special Operations Command (ASOC), Naval Special Warfare Command (NSW), Air Force Special Operations Command (AFSOC), Marine Corps Forces Special Operations Command (MARSOC), and Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC). Each special operations command (SOC) is capable of conducting its own operations and has responsibility for its forces.[23] ASOC is responsible for Special Forces (SF), Ranger, Army SO aviation, SO MISO, and SO civil affairs (CA) units. NSW is responsible for SEAL, SEAL delivery vehicles, and special boat teams. AFSOC is responsible for SO flying units (including unmanned aircraft systems), special-tactics elements (including combat control, para-rescue, SO weather, and select tactical air-control party [TACP] units), and aviation FID units. MARSOC has responsibility for Marine SO battalions. JSOC is responsible for the study of SO requirements and techniques, planning, carrying out SO exercises, and the development of joint special-operations tactics.

C. Strategic Environment

The purpose of a national-security strategy is to guide for achieving a high level of security for the nation. To achieve this purpose, it examines the strategic environment, sets objectives, and articulates plans. Therefore, the strategic environment includes all national power elements—diplomatic, informational, military, and economic. Policymakers attempt to combine and balance all these elements to achieve the objectives of security strategy.

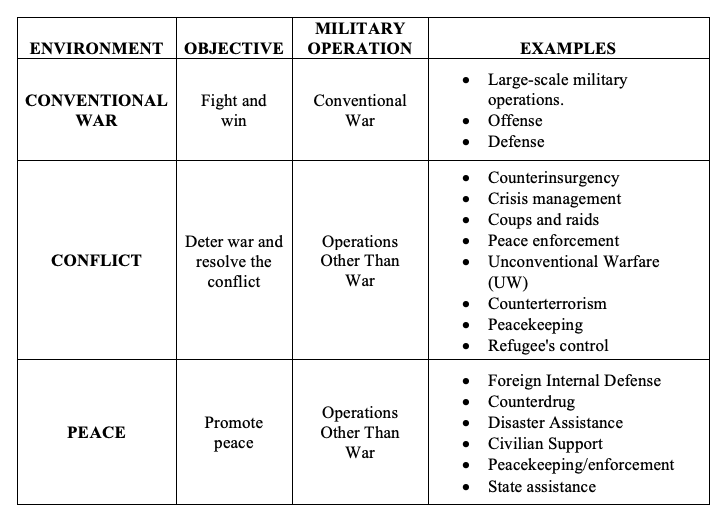

Military activities and applications vary significantly according to the features of an operational environment. Additionally, each military operation can vary in scope, objective, and combat intensity.[24] Table 1 displays a range of military operations at all levels of the strategic environment.

SOF can be employed at all levels within the strategic environment and provide strategic utility. In peacetime, SOF, with their warrior diplomat skills, could shape the operational environment and prevent likely conflicts between nations or groups in support of U.S foreign policy. In conflict, SOF can conduct various missions linked with crisis response and limited contingencies, such as civil-military operations (CMO), foreign internal defense (FID), and security forces assistance (SFA).[25] Major operations and campaigns require joint forces and include various types of operations. SOF can shape the operational environment, provide a broad range of options for decision-makers, and conduct direct-action missions supporting CF.

In the current security environment, small wars have become increasingly widespread. Regional conflicts in the Balkans, the Caucuses, Iraq, and Afghanistan are well-known examples. Hence, military missions such as counterinsurgency, foreign internal defense, local forces training, unconventional warfare, civil affairs, and military information support operations (MISO) are necessary and important. SOF is able to communicate with the host-nation officials and local people, taking the war to the enemy and fighting in a way that undermines the enemy’s natural advantage.[26]

D. Strategic Utility

This article employs the term “strategic utility” as a measure of an operation’s contribution to the outcome of a campaign or war.[27] This contribution can originate both directly, such as the killing of an enemy leader, and indirectly, such as eliminating the conditions that allow violent, extremist organizations (VEOs) to take safe haven in uncontrolled areas.[28] SOF are specifically organized, trained, and equipped to conduct and support special operations. They provide strategic utility, counter conventional and unconventional threats to national security, and conduct specific missions that conventional forces cannot. The absence of a universally accepted definition of SO makes it difficult to assess SOF’s strategic utility. It is unrealistic to evaluate strategic utility in a general way since the strategic value of SOF is limited to specific types of campaigns and individual cases. Therefore, SO and SOF must be considered in relation to a war or conflict as a whole.[29] In other words, the conditions and environments in which SOF are employed are key in assessing their strategic value. These strategic environments can vary from peace to war and be categorized as peacetime, conflict, and war. To provide strategic utility and counter the security problems, SOF needs a coherent strategic concept. This concept must accurately and clearly identify the roles, missions, capabilities, and limitations of SOF. History is filled with many cases in which SOF was misused; a coherent strategic concept, derived from a clear policy, could prevent such misemployments. To employ SOF properly, policymakers and military leaders must have a common understanding of SO’s strategic utility.

The USSOCOM posture statement for 2006 emphasizes that “there is no ‘silver bullet’ for success.”[30] It is evident that SO can have strategic utility only if they succeed.[31] Although tactical success is required for strategic utility, it is not sufficient to achieve high strategic utility. For example, in 1942, the British raid’s primary objective on St. Nazaire—Operation Chariot—was to destroy the dry dock.[32] Although the raid was accomplished successfully, it had little effect in the theater of war since it did not prevent Germany from functioning in the North Sea against Allied convoys bound for Russia.[33] Furthermore, there are conditions for success. In his article, “Handfuls of Heroes on Desperate Ventures: When do Special Operations Succeed?” Colin Gray claims that to promote success in the conduct of special operations, SOF need:

- To fit the demands of policy.

- A tolerant political and strategic culture.

- Political and military patrons who understand their strategic value.

- To be assigned feasible objectives.

- To be directed by a strategically functioning defense establishment.

- The flexibility of mind, and particularly an unconventional mentality.

- To provide unique strategic services.

- To find and exploit enemy vulnerabilities.

- Technological assistance.

- Tactical competence (preferably tactical excellence).

- A reputation for effectiveness.

- A willingness to learn from history.[34]

According to Gray, the strategic utility of SOF can be grouped into two categories. First, the economy of force and expansion of choice are the critical “master claims.” In the second, innovation, morale, showcasing of competence, reassurance, humiliation of the enemy, control of escalation, and shaping of the future are the other claims.[35] The economy of force is one of the most important principles of a military campaign. SOF is well suited to this principle of war because “special operations can achieve significant results with limited forces.”[36] SOF can be employed as force multipliers for conventional units on the battlefield to achieve different objectives such as to open a door, hasten victory, and retard defeat. SOF can operate directly against enemy targets through direct assaults on strategic targets, killing or capturing an enemy’s major leaders, and other actions that significantly impact the enemy.[37] “Economy of force” addresses mostly the supporting role, direct mission, and commando skills of SOF.

The expansion of the options available to political and military leaders focuses on SOF’s unconventional skills, which is its main strategic contribution.[38] SOF can be used to achieve military, diplomatic, economic, and informational objectives. During peacetime or conflict, SOF can rescue hostages or conduct counterterrorism strikes, unconventional warfare, psychological operations, and foreign internal defense, which increases the choices available to policymakers. During the war, SOF can conduct direct-action missions against enemy targets and provide more options to military leaders. Gray emphasizes that “the availability of special operations capability means that a country can use force flexibly, minimally, and precisely.” The expansion of choice addresses both the commando and the warrior-diplomat roles of SOF. Policymakers and military leaders can utilize SOF both directly and indirectly.

To do so effectively, the roles and missions that SOF undertakes must be clearly understood by policymakers and military leaders alike. They can employ SOF properly only if they fully understand what each organization is optimally designed to do.

III. SOF Roles and Missions

“The Department of Defense defines military roles in legal terms as the broad and enduring purpose for which Congress established the Services and the Special Operations Command (SOCOM), and missions as the more specific tasks assigned to the combatant commanders, which would include the commander of SOCOM.”[39] Although there is general agreement among academics, policymakers, and the SOF community about the need for SOF, extensive discussions persist regarding what makes SOF “special” or “elite” and what are their roles and missions.[40] “These disagreements are reflective of a division of opinion within the special-ops community as to whether they ought to be shooters or social workers.”[41] While some place greater emphasis on SOF’s direct-action missions and supporting roles, others stress SOF’s independent roles and indirect-action skills. This debate stems from the complex and diverse nature of SOF.

A. Special Operations Core Activities

Each element of SOF has different skills and orientations, and SOF has many different kinds of missions. SOF are equipped and organized to conduct the following twelve core activities: direct action, special reconnaissance, counterproliferation of weapons of mass destruction, counterterrorism, unconventional warfare, foreign internal defense, security force assistance, hostage rescue and recovery, counterinsurgency, foreign humanitarian assistance, military information support operations, and civil affairs operations.[42] As U.S. Special Forces Command notes, “these missions make Special Forces unique in the U.S. military because they are employed throughout the three stages of the operational continuum: peacetime, conflict, and war.”[43]

Direct Action (DA)

Direct Action (DA) involves short duration strikes and other small-scale offensive actions conducted as special operations in hostile, denied, or diplomatically sensitive environments, employing specialized military capabilities to seize, destroy, capture, or exploit designated targets. For example, USSOF teams conducted the Son Tay raid (Operation Ivory Coast) to rescue American soldiers in North Vietnam during the Vietnam War.

Special Reconnaissance (SR)

Special Reconnaissance (SR) entails reconnaissance and surveillance actions conducted as special operations in a hostile, denied, or diplomatically sensitive environments to collect or verify information of strategic or operational significance, employing military capabilities not normally found in conventional forces. SR may include collecting information on the activities of an actual or potential enemy or securing data on the meteorological, hydrographical, or geographical characteristics of a particular area. For example, in the first Gulf War, Special Forces conducted SR to find mobile Iraqi SCUD launchers.

Counterproliferation (CP) of Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMDs)

Counterproliferation (CP) of Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMDs) refers to actions taken to prevent, limit, or defeat the threat and/or use of WMDs against American forces, allies, and partners. Stopping a suspected ship on the high seas to search for WMDs is an example of a counterproliferation operation.[44]

Counterterrorism (CT)

Counterterrorism (CT) is defined as actions taken directly against terrorist networks and indirectly to influence and render global and regional environments inhospitable to terrorist networks. CT includes intelligence operations, hostage rescue, and recovery of sensitive materials from terrorist groups. One well-known example of CT is Operation Entebbe, which was a hostage rescue carried out by Israeli commandos at Entebbe Airport in 1976.[45]

Unconventional Warfare (UW)

Unconventional Warfare (UW) is those activities conducted to enable a resistance movement or insurgency to coerce, disrupt, or overthrow a government or occupying power by operating by, with, or through indigenous or surrogate forces in a denied area. UW entails guerilla warfare, subversion, sabotage, and intelligence activities. After the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait, special forces trained and worked with Kuwaitis and help them establish an SF battalion and commando brigade.[46]

Foreign Internal Defense (FID)

Foreign Internal Defense (FID) refers to activities that support a host nation’s internal defense and development (IDAD) strategy, designed to protect against subversion, lawlessness, insurgency, terrorism, and other threats to their security, stability, and legitimacy. For example, after the U.S involvement in Vietnam, Special Forces were employed in an advisory mission with the South Vietnamese military.

Security Force Assistance (SFA)

Security Force Assistance (SFA) refers to activities that focus on the inextricably linked governmental sectors of security and justice. SFA includes activities of organizing, training, equipping, rebuilding, and advising various components of foreign security forces.

Hostage Rescue and Recovery

Hostage Rescue and Recovery are sensitive crisis response missions in response to terrorist threats and incidents.

Counterinsurgency (COIN)

Counterinsurgency (COIN) refers to comprehensive civilian and military efforts taken to defeat the insurgency and address any core grievances. With combat skills, experience, cultural awareness, and language skills, which allow them to work by, with, and through indigenous and host-nation security forces, SOFs are particularly suitable for COIN operations or campaigns. Between 1954 and 1964, French security forces carried out COIN campaigns and operations against the Front de Liberation Nationale (FLN) in Algeria.

Foreign Humanitarian Assistance

Foreign Humanitarian Assistance is a range of DOD humanitarian activities conducted outside the US and its territories to relieve or reduce human suffering, disease, hunger, or privation.

Military Information-Support Operations (MISO)

Military Information-Support Operations (MISO) are operations to convey selected information and indicators to foreign audiences to influence their emotions, motives, objective reasoning, and, ultimately, the behavior of foreign governments, organizations, groups, and individuals. MISO is vital for special operations and SOF missions, particularly for irregular conflicts that focus on ideological and social-political dimensions such as FID, COIN, CT, and UW.

Civil-Affairs Operations (CAO)

Civil-Affairs Operations (CAO) are operations that enhance the relationship between military forces and civil authorities in localities where military forces are deployed. For example, during the Granada intervention, the 96th Civil-Affairs Battalion restored communication systems, cared for displaced people, and rehabilitated the school system, public utilities and public works, and water and sewage systems.[47]

B. SOF Direct and Indirect Missions

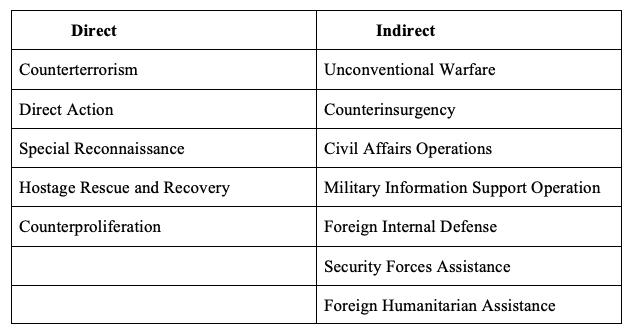

SOF receive specialized training for both direct and indirect military operations.[48] SOCOM has an essential role in recommending which role is more strategically useful for a given situation.

Examples of indirect employment are training, advising, equipping, and employing indigenous forces. Some missions are more appropriately designed to be direct actions against enemy targets due to the nature of the threat and preferred U.S. strategy.[49] Three factors must be taken into account when determining new roles and missions: the nature of the threats and security environment, the national-security strategy, and the nature of the forces themselves.[50]

There appears to be more beneficial in the current security environment if SOF trains, supports, and advises local forces to accomplish a mission indirectly.[51] One can categorize currently recognized SOF missions as follows:

Table 2. SOF Direct and Indirect Missions (After Tucker and Lamb, 2007) [52]

In complex situations, direct and indirect missions are often conducted together. The categories are beneficial, however. For example, SOCOM admits that “unconventional warfare is primarily conducted by, with, or through indigenous or other non-U.S. forces.”[53] There is a tacit acknowledgment that U.S. forces may conduct guerrilla warfare. The same objective might well be achieved through the indirect use of indigenous forces.

In most cases, one can see that direct or indirect categorization helps understand the mission. Both approaches require some combination of SOF warrior-diplomat and commando skills. In direct operations, they tend to rely more on commando capabilities. When indirect means are used, they rely more on political, cultural, and linguistic skills.[54]

Direct assaults, hostage-rescue operations, kidnapping, and killing the enemy’s foremost leaders are examples of actions potentially executed by SOF that significantly impact a campaign.[55] The direct approach allows for more control over outcomes. In other words, the success of the operation results in a positive effect and failure in a negative impact. Operation Eagle Claw, which was carried out in 1980 to rescue hostages at the U.S. embassy in Tehran, ended in failure. The United States has lost its citizens and military vehicles. Iran shared photos of the downed plane, helicopter, and other photos of the operation with the press, making the world public aware. As a result, the failure of the operation deeply damaged U.S. prestige worldwide.

On the contrary, Osama bin Laden was killed in a successful operation led by the CIA and JSOC in Abbottabad on 2 May 2011. Operation Neptune Spear has increased the importance of SOF and the prestige of the United States. SOF came of age with this successful raid, proved its strategic utility. The operation quickly turned into a propaganda tool, and many publications, news, and films were put forward, such as SEAL Team Six, Zero Dark Dirty.[56]

On the other hand, in solving problems, using larger forces directly could cause resistance from a foreign population, which is problematic.[57] The Operation Neptune Spear, which was carried out in 2011, negatively affected the relationship between Pakistan and the USA.[58] It also caused discussions in the international arena on whether the operation was legal or not. Pakistani officials denounced the US, stating that the US had not been informed about the operation and Bin Laden’s presence in Pakistan. Besides, they stated that the operation violated Pakistan’s sovereignty. However, US officials argued that the raid and Bin Laden’s killing were legal.[59] Using SOF, employed indirectly, can be advantageous, as working through foreign forces reduces the domestic resources and political commitments of the United States. SOF can provide an economy of force and offer a disproportionate return on military investment. However, the indirect approach has some disadvantages, such as achieving goals more slowly and with less certainty.[60]

C. SOF Independent and Supporting Roles

In independent SOF operations, SOF takes part as the primary force. Conventional forces may support SOF; however, SOF principles and preferences are applied in independent SOF operations. An example of a SOF independent role would be conducting a special reconnaissance operation to collect information on a critical enemy target. Another example of an independent role would be a raid of significant enemy targets for political effect. The raid, which Bin Laden was killed, has aroused great repercussion in the international arena and brought prestige to the United States. SOF were the leading forces and was supported by the other US agencies in the Operation Neptune Spear.

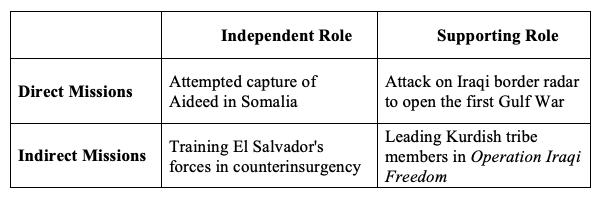

In contrast, when the roles change and SOF support conventional forces, SOF missions aim to help the achievement of conventional force objectives.[61] A well-known example of SOF’s supporting role is the German glider attack on Eben Emael in World War II, one of the most decisive victories in the history of special operations.[62] With this successful assault, German conventional forces were able to advance into Belgium. It is obvious that USSOF is capable of conducting operations independently or in support of conventional forces, both directly and indirectly.

Table 3. Independent and Supporting Roles (From Tucker and Lamb, 2007)[63]

The employment of SOF independently to capture Aideed was a direct-action mission. Working by, with, and thorough El Salvador’s forces in COIN was a way of fighting the enemy indirectly, performed independently by SOF. At the beginning of the first Gulf War, to support the general-purpose forces, SOF conducted a raid on the Iraqi border radar, which was a direct-action mission. In Iraq, SOF led Kurdish forces in support of a conventional-forces effort.[64] In light of these historical cases, one can conclude that different conditions determine SOF roles and missions. As mentioned above, the threat and security environment, strategy choices, and the nature of the forces themselves are critical for SOF’s roles and missions.

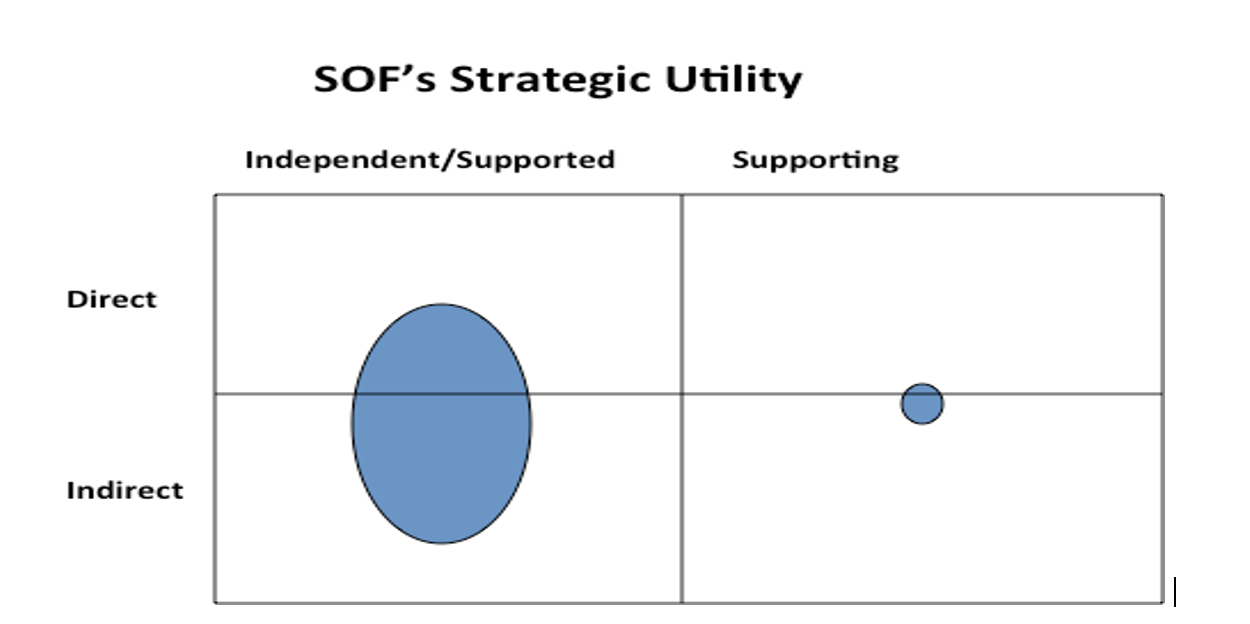

SOF uses methods to achieve objectives, which are different from those used by conventional forces.[65] SOF “conduct operations that are outside the realm and tactics of the conventional battlefield.”[66] Given the uniqueness of SOF, their more excellent strategic utility rests in their independent role, where they are the primary effort. They have less strategic value in a supporting role since SOF assists conventional forces. However, the U.S. military wages war by deploying more massive formations to the battlefield with advanced technology and weapon systems because policymakers and senior military leaders prefer lower-risk strategies established around conventional forces.[67] Parallel to this argument, SOF is primarily deployed in support of GPF with their direct-action skills since it is less risky and provides more control over the outcome. As evidenced in most historical cases, a SOF in a supporting role using direct-action skills only accelerates victory or delays defeat.

Moreover, using SOF in support of GPF directly increases their costs relative to their strategic contributions. On the battlefield, the ambiguity, friction, and massive combat power arrangement relegated SOF’s ability to conduct special operations, decreasing their strategic utility.[68] The strategic contribution of SOF is limited under such conditions. As a result, SOF’s strategic utility can be depicted in Figure 1:

- Figure 1. SOF’s Strategic Utility (From Hy Rothstein)[69]

To summarize, “SOF’s strategic value rests in their ability to counter unconventional threats both directly and indirectly and take the lead in doing so… SOF’s indirect role is comparatively more important than its direct role.”[70] When one considers using SOF to accomplish a strategic objective, the following issues must be evaluated: the appropriate SOF skill sets, the advantages of using SOF directly and/or indirectly, and whether SOF should be the leading or a supporting effort. The assessment of SOF’s role and missions depends on the nature of the threats and the security environment, the national security strategy, and the nature of the forces themselves.

IV. Recent Developments

Since 2014, several key developments have shaped the role and strategic utility of SOF. The rise of great power competition, particularly with China and Russia, has prompted a reevaluation of SOF missions. The U.S. Department of Defense emphasizes adapting SOF to hybrid warfare and gray zone conflicts, blending conventional and unconventional tactics without triggering full-scale war. [71] [72]

The conflict in Ukraine highlights SOF’s evolving role. Ukrainian SOF, supported by Western countries, have become a cornerstone of Ukraine’s defense against Russian aggression. The U.S. and other NATO members have provided extensive training, equipment, and operational support, significantly enhancing Ukrainian SOF capabilities.[73]

Technological advancements, including artificial intelligence (AI) and cyber capabilities, are increasingly integrated into SOF operations. These technologies enhance SOF’s ability to operate in contested environments and provide policymakers with more flexible and precise tools for achieving strategic objectives.[74]

V. Conclusions and Recommendations

After the September 11 attacks, irregular threats and terrorism became the top security issues of the US. These threats were primarily responded to with SOF. Although the use of SOF has increased, the way it is used has not changed much. Direct missions and supporting roles have been mostly favored. Indirect missions and independent employment have been ignored. [75] Such deployment has reduced the strategic benefit of SOF and limited its contribution.

SOF can’t benefit unless its strengths and weaknesses are taken into account by decision-makers. The value of SOF depends on some criteria. These are the security environment, the National Security Strategy, the structure of forces. If these criteria are taken into account together, SOF will be the magic tool for policymakers. However, the lack of knowledge and understanding about the issue of SOF strategic value remains. One of the most important reasons for this problem is the SO broad and vague definition. It is also a misunderstanding and evaluation of SO. It is essential to establish a clear and common opinion about SO.

Institutional constraints, leadership deficiencies, and insufficient knowledge of SOF capabilities have led to the misuse of SOF as a strategic asset for current threats. [76] SOF should primarily conduct both indirect and direct missions independently or as a supported unit. This arrangement will increase its potential as a strategic tool. Moreover, the indirect role would serve better than a direct role. The value of SOF for Homeland Security and Defense lies in its independent or at least supported usage.

As a result, the strategic utility of USSOF lies in the use of independent and primary force. At the same time, indirect missions result in more effective results than direct missions. While using these strategic tools, decision-makers should assign them more as an independent and leading forces. Although indirect tasks performed by SOF give results in a long time, they should be preferred primarily.

VI. List of References

Adams, Thomas K. U.S Special Operations Forces in Action: The Challenge of Unconventional Warfare, London: Frank Cass, 1998.

Alvin and Toffler, Heidi. War and anti-war: survival at the dawn of the 21st century, Boston: Little, Brown, 1993.

Andres, Richard B. Craig Wills, and Thomas E. Griffith. “Winning with Allies: The Strategic Value of the Afghan Model,” International Security Vol. 30, No. 3, (Winter 2005).

Arquilla, John ed. From Troy to Entebbe: Special Operations in Ancient and Modern Times, Lanham, NY: University Press of America, 1996.

Biddle, Stephen D. “Allies, Air Power, and Modern Warfare: The Afghan Model in Afghanistan and Iraq,” International Security Vol. 30, No. 3, (Winter 2005).

Biddle, Stephen D. Special Forces and the Future of Warfare: Will SOF Predominate in 2020?, Strategic Studies Institute U.S. Army War College, 24 May 2004, http://www.offnews.info/downloads/2020special_forces.pdf

Bilgin H. and Goztepe K. “Strategic Utility Analysis of Special Operations Forces Applying Game Theory,” Journal of Military and Information Science,1(1), (2013): 14-25.

Cohen, Eliot A. Commandos and Politicians: Elite Military Units in Modern Democracies Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1978.

Connor, Ken. Ghost Force: The Secret History of the SAS, London: Cassell, 2004.

Finlan, Alastair. Special Forces, Strategy and the War on Terror, New York: Routledge, 2008.

Gray, Colin. “Handfuls of Heroes on Desperate Ventures: When Do Special Operations Succeed?”, Parameters Vol. 29, (Spring 1999).

Gray, Colin. Explorations in Strategy, Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1996.

Horn, Bernd. When Cultures Collide: The Conventional Military/SOF Chasm, Canadian Military Journal, Vol. 5, Vol. 3 Autumn 2004.

Horn, Bernd. Theoretical Foundation to Understanding Special Operations Forces, in Bernd Horn and Tony Balasevicius (eds), Casting Light on the Shadows: Canadian Perspectives On Special Operations Forces (Kingston, Ontario: Defense Academy Press, 2007),

Kiras, James. Special Operations and Strategy from World War II to the War on Terrorism. London; New York: Routledge, 2006.

Kraag, Andy and Larssen, Brage. The “Start Game” of Coalitions, DA 4410 Models of Conflict Student Pamphlet.

Lamb, Christopher. Perspectives on Emerging SOF Roles and Missions, Special Warfare, July 1995.

Lambakis, Steven. “Forty Selected Men Can Shake the World: The Contributions of Special Operations to Victory,” Comparative Strategy Vol. 13, No. 2, April 1994.

Mahla, Philip L. Riga, Christopher, An Operational Concept For The Transformation Of SOF into a Fifth Service, http://edocs.nps.edu/npspubs/scholarly/theses/2003/Jun/03Jun_Mahla.pdf.

Marquis, Susan L. Unconventional Warfare: Rebuilding U.S. Special Operations Forces. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution, 1997.

McRaven, William H. Spec Ops: Case Studies in Special Operations Warfare Theory and Practice, Novato, CA: Presidio Press, 1996.

Naylor, Sean. Not a Good Day to Die: The Untold Story of Operation Anaconda, New York: Berkeley Books, 2005.

Neillands, Robin. In the Combat Zone: Special Forces since 1945, London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1997.

Ohad, Leslau. “Worth the Bother? Israeli Experience and the Utility of Special Operations Forces”, Contemporary Security Policy, 31:3, 2010.

O’Hanlon, Michael E. “A Flawed Masterpiece,” Foreign Affairs, Vol. 81, No. 3, May/ June 2002,http://people.reed.edu/~ahm/Courses/Reed-POL-359–2011-S3_WTW/Syllabus/EReadings/12.1/12.1.OHanlon2002A-flawed.pdf

Pratt, Christopher D. Permanent Presence for the Persistent Conflict: An Alternative Look at the Future of Special Forces, http://edocs.nps.edu/npspubs/scholarly/theses/2009/Jun/09Jun%5FPratt.pdf.

Rothstein, Hy S. Afghanistan &The Troubled Future of Unconventional Warfare, Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2006.

Rothstein, Hy S. DA 3880 History of Special Operations Resources, 2006.

Stanley Sandler, Glad to See Them Come and Sorry to See Them Go: A History of U.S. Army Civil Affairs and Military Government 1775–1991, (U.S. Army Special Operations Command History and Archives Division)

Suvorov, Viktor. Spetsnaz: The Story Behind the Soviet SAS, London: Hamish Hamilton, 1987.

Tucker, David, and Christopher J. Lamb. United States Special Operations Forces. New York: Columbia University Press, 2007.

Tugwell, Maurice and David Charters, Special Operations and the Threats to United States Interests in the 1980s, in Frank R. Barnett, B. Hugh Tovar, and Richard H. Shultz (eds), Special Operations in U.S. Strategy Washington DC: National Defense University Press, 1984, http://permanent.access.gpo.gov/lps53477/Spec%20Ops%20in%20US%20Strat%20-%20Oct%2088/soist.pdf.

USSOCOM, Joint Publication 3–05, Special Operations, 2011.

United States Special Operations Command Posture Statement: Right Place, Right Time, Right Adversary, 2006,

http://www.fas.org/irp/agency/dod/socom/posture2006.pdf.

United States Special Operations Forces Posture Statement, 2003–2004.

United States Army Special Forces Command (A) Fact Sheet, http://www.soc.mil/SF/factsheets.htm.

Vandenbroucke, Lucien S. Perilous Options: Special Operations as an Instrument of U.S. Foreign Policy, New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

White, Terry. Swords of Lightning: Special Forces and the Changing Face of Warfare, London: Brassey’s, 1992.

Clementine G. Starling and Alyxandra Marine. “Stealth, Speed, and Adaptability: The Role of Special Operations Forces in Strategic Competition,” Atlantic Council, 2024.

“Rediscovering the Value of Special Operations,” National Defense University Press, 2024.

“Hunting the Invader: Ukraine’s Special Operations Troops,” Center for European Policy Analysis (CEPA), 2022.

“Developments in Special Operations Forces (SOF),” Armada International, 2017.

[1] Alvin and Heidi Toffler, War and anti-war: survival at the dawn of the 21st century, (Boston: Little, Brown, 1993), 90.

[2] Bilgin H. and Goztepe K., (2013). Strategic Utility Analysis of Special Operations Forces Applying Game Theory, Journal of Military and Information Science, 1(1), 14-25.

[3] Mahla and Riga, An Operational Concept for The Transformation of SOF into a Fifth Service, 2.

[4] Tucker and Lamb, United States SOF, 177.

[5] James Kiras, Special Operations and Strategy from World War II to the War on Terrorism (London; New York: Routledge, 2006), 3; Stephen D. Biddle, Allies, Air Power, and Modern Warfare: The Afghan Model in Afghanistan and Iraq, International Security, Vol. 30, No. 3 (Winter 2005–06), 161–162; Michael E. O’Hanlon, A Flawed Masterpiece, Foreign Affairs, Vol. 81, No. 3 (May/ June 2002), 54–57; Stephen D. Biddle, Special Forces and the Future of Warfare: Will SOF Predominate in 2020?, Strategic Studies Institute U.S. Army War College, (24 May 2004), 2-3.

[6] Ohad, Worth the Bother? 511.

[7] Tucker and Lamb, United States SOF, 174-177; Thomas K. Adams, US Special Operation Forces in Action: The Challenge of Unconventional Warfare (London/Portland, OR: Frank Cass Publishers, 1998), 24; Alastair Finlan, Special Forces, Strategy, and the War on Terror (New York: Routledge, 2008), 12; Richard B. Andres, Craig Wills, and Thomas E. Griffith, Winning with Allies: The Strategic Value of the Afghan Model, International Security, Vol. 30, No. 3 (Winter 2005–06), 124–126.

[8] Adams, US Special Operations Forces in Action, 24; Viktor Suvorov, Spetsnaz: The Story Behind the Soviet (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1987); Ken Connor, Ghost Force: The Secret History of the SAS (London: Cassell, 2004); Sean Naylor, Not a Good Day to Die: The Untold Story of Operation Anaconda (New York: Berkeley Books, 2005).

[9]Bernd Horn, When Cultures Collide: The Conventional Military/SOF Chasm, (Canadian Military Journal, Vol. 5, Vol. 3 Autumn 2004), 3–16; Eliot A. Cohen, Commandos and Politicians: Elite Military Units in Modern Democracies (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1978); Susan L. Marquis, Unconventional Warfare: Rebuilding US Special Operations Forces (New York: Brookings Institution Press, 1997).

[10] Lucien S. Vandenbroucke, Perilous options: special operations as an instrument of U.S. foreign policy, New York : Oxford University Press, 1993; William H. McRaven, Spec Ops: Case Studies in Special Operations Warfare Theory and Practice (Novato, CA: Presidio Press, 1996); Colin S. Gray, Explorations in Strategy (Westport, CT: Green- wood Press, 1996); Colin S. Gray, Handfuls of Heroes on Desperate Ventures: When Do Special Operations Succeed? (Parameters, Vol. 29 Spring 1999), 2–24.

[11] Bernd Horn, Theoretical Foundation to Understanding Special Operations Forces,in Bernd Horn and Tony Balasevicius (eds), Casting Light on the Shadows: Canadian Perspectives on Special Operations Forces (Kingston, Ontario: Defense Academy Press, 2007), 20-21.

[12] U.S. Special Operations Forces (SOF): Background and Issues for Congress, 6 January 2017, 1, https://apps.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/1024461.pdf

[13] Colin Gray, Explorations in Strategy (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1996), 149.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Kiras, Special Operations and Strategy, 5.

[16] William H. McRaven, Spec Ops: Case Studies in Special Operations Warfare Theory and Practice, (Novato, CA: Presidio Press, 1996), 2.

[17] Lucien S. Vandenbroucke, Perilous options: special operations as an instrument of U.S. foreign policy, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 8.

[18] Vandenbroucke, Perilous options, 4.

[19] Maurice Tugwell and David Charters, Special Operations and the Threats to United States Interests in the 1980s, in Frank R. Barnett, B. Hugh Tovar, and Richard H. Shultz (eds), Special Operations in US Strategy (Washington DC: National Defense University Press, 1984), 34, http://permanent.access.gpo.gov/lps53477/Spec%20Ops%20in%20US%20Strat%20-%20Oct%2088/soist.pdf,

[20] USSOCOM, Joint Publication 3-05, Special Operations, (2011), II-1

[21] Department of Defense Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms, 8 November 2010 http://www.dtic.mil/doctrine/new_pubs/jp1_02.pdf,

[22] USSOCOM, Joint Publication 3-05, Special Operations, (2011), II-1.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid., I-3.

[25] Ibid., I-3.

[26] Ibid., I-4.

[27] Gray, Explorations in Strategy, 164.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Ibid., 143.

[30] United States Special Operations Command Posture Statement: Right Place, Right Time, Right Adversary, 2006, http://www.fas.org/irp/agency/dod/socom/posture2006.pdf.

[31] Gray, Explorations in Strategy, 141.

[32] McRaven, Spec Ops, 142.

[33] Ibid., 143.

[34] Gray, Handfuls of Heroes, 15.

[35] Gray, Explorations in Strategy, 168.

[36] Ibid.

[37] Steven Lambakis, “Forty Selected Men Can Shake the World”: The Contributions of Special Operations to Victory, Comparative Strategy, Vol. 13, No. 2 (April 1994), 212–213.

[38] Ohad, Worth the Bother?, 513.

[39] Tucker and Lamb, United States SOF, 143.

[40] Christopher D. Pratt, Permanent presence for the persistent conflict: an alternative look at the future of special forces, http://edocs.nps.edu/npspubs/scholarly/theses/2009/Jun/09Jun%5FPratt.pdf.

[41] Thomas K. Adams, US Special Operation Forces in Action: The Challenge of Unconventional Warfare (London/Portland, OR: Frank Cass Publishers, 1998), 8.

[42] The descriptions of SOF missions are based on USSOCOM, Joint Publication 3-05, Special Operations, (2014), 5-20 and United States Special Operations Forces Posture Statement (2003-2004), 36-37.

[43] U.S Army Special Forces Command (A) Fact Sheet, http://www.soc.mil/SF/factsheets.htm

[44] Tucker and Lamb, United States SOF, xviii.

[45] Chaim Herzog, The War Against Terrorism: Entebbe, from Troy to Entebbe: Special Operations in Ancient and Modern Times, ed. John Arquilla, (London/New York: University Press of America, 1996), 335.

[46] Tucker and Lamb, United States SOF, xviii.

[47] Stanley Sandler, Glad to See Them Come and Sorry to See Them Go: A History of U.S. Army Civil Affairs and Military Government (U.S. Army Special Operations Command History and Archives Division), 374-375.

[48] Terry White, Swords of Lightning: Special Forces and the Changing Face of Warfare, (London: Brassey’s, 1992), 1.

[49] Tucker and Lamb, United States SOF, 153.

[50] Christopher Lamb, Perspectives on Emerging SOF Roles and Missions, Special Warfare (July. 1995), 2.

[51] Richard B. Andres, Craig Wills, and Thomas E. Griffith, Winning with Allies: The Strategic Value of the Afghan Model, International Security, Vol. 30, No. 3 (Winter 2005–06), 124–126.

[52] Tucker and Lamb, United States SOF, 153.

[53] Ibid., 154.

[54] Ibid.

[55] Steven Lambakis, “Forty Selected Men Can Shake the World: The Contributions of Special Operations to Victory”, Comparative Strategy, 212–213.

[56] Paul B. Rich, Cinema and Unconventional Warfare in the Twentieth Century, (London:Bloomsbury Academic, 2018), 41.

[57] Lambakis, “Forty”, 212-213.

[58] Syed Hussain Shaheed & Shahid, “Ali Operation Geronimo: Assassination and Its Implications on the US-Pakistan Relations, War on Terror, Pakistan and Al-Qaeda”, South Asian Studies Vol. 26, No. 2, (July-December 2011), 349-365.

[59] John R. Crook. “Contemporary Practice of The United States Relating to International Law.” The American Journal of International Law 105, no. 3 (2011): 568-611. Accessed April 7, 2021. doi:10.5305/amerjintelaw.105.3.0568.

[60] Lambakis, “Forty”, 156.

[61] Lambakis, “Forty”, 158.

[62] McRaven, Spec Ops, 55.

[63] Tucker and Lamb, United States SOF, 158.

[64] Ibid.

[65] Leslau. Worth the Bother?, 511.

[66] Marquis, Unconventional Warfare, 46.

[67] Tucker and Lamb, United States SOF, 159

[68] Leslau. Worth the Bother?, 513.

[69] Hy Rothstein, DA 3880 History of Special Operations’ Resources.

[70] Tucker and Lamb, United States SOF, 177.

[71] Clementine G. Starling and Alyxandra Marine, Clementine G. Starling and Alyxandra Marine. “Stealth, Speed, and Adaptability: The Role of Special Operations Forces in Strategic Competition,” Atlantic Council, 2024.

[72] “Hunting the Invader: Ukraine’s Special Operations Troops,” Center for European Policy Analysis (CEPA), 2022.

[73] “Rediscovering the Value of Special Operations,” National Defense University Press, 2024.

[74] “Developments in Special Operations Forces (SOF),” Armada International, 2017.

[75] Tucker and Lamb, United States SOF, 174.

[76] Mahla and Riga, An Operational Concept For The Transformation Of SOF into a Fifth Service, 2.

Hasan Bilgin is a highly accomplished military professional with a distinguished background in special operations, strategic planning, and leadership. With extensive experience in various key staff and command roles, Hasan has demonstrated expertise in managing high-stakes missions, coordinating complex operations, and developing innovative solutions for defense and security challenges.

Currently serving as a Defense and Security Researcher and Entrepreneur in Belgium, Hasan acts as a Subject Matter Expert (SME) in various projects. His contributions to academic research on defense and security have been notable, with multiple publications and collaborations with international experts in the field.

Prior to his NATO assignment as a Civil-Military Relations Officer at NATO Allied Joint Force Command Naples (JFC), Hasan served in various leadership capacities within the Turkish Armed Forces.

Hasan holds a Master of Science in Defense Analysis from the Naval Postgraduate School, California, and a Master of Arts in Defense and Security Studies from the Army War College, Istanbul. He has received numerous awards and certifications for his contributions to military education and research, reflecting his dedication to continuous learning and professional development.

With a proven track record of excellence in both military and academic spheres, Hasan Bilgin brings a unique blend of practical experience and scholarly insight to the field of Security and Defense Policy Studies. His passion for innovation and commitment to mission success make him an asset to any organization seeking to address today's complex security challenges.