[Murat Çalışkan]

Hybrid warfare has been a popular concept since it was first publicly used in 2005 in defense discussions. However, the popularity of the concept has always been accompanied with criticism. It has been targeted mainly for the ambiguity and broadness of its definition. Moreover, the definition has evolved considerably throughout the last decade. This paper aims to measure the ambiguity of the concept and the impact of Russia’s operations on its evolution. Based on the content analysis of 230 media items, it concludes that it is an ambiguous concept since 68% of the time the authors suggest another concept while using hybrid warfare.

Introduction

The term “hybrid warfare” was first used in the master theses of military practitioners in the US at the end of 1990s.1 In 2005, the term caught the attention when Lieutenant General James N. Mattis and retired Lieutenant Colonel Frank Hoffman argued, in an article in the US Naval Institute Magazine, that future wars will present a combination of emerging challenges—namely traditional, irregular, catastrophic, and disruptive, rather than separate challenges as reflected in the US 2005 National Defence Strategy (NDS). They preferred to name this ‘unprecedented’ synthesis “Hybrid Warfare.”2 Since then, this term has gradually gained traction in the defence community, with Frank Hoffman eventually being the one to develop and popularize the concept of hybrid warfare over a series of publications.3 Today, the concept of hybrid warfare/hybrid threats is considered as the main challenge that the Western countries must address.

A review of literature demonstrates that the definition of hybrid warfare has evolved considerably since Hoffman’s first postulation. While Hoffman’s hybrid warfare denotes a an operational/tactical level convergence of distinct modes of warfare in the same battlespace,4 it has mutated to a broader definition particularly after Russia’s annexation of Crimea which denotes the simultaneous use of military and non-military means even at higher levels. NATO described hybrid threats as “combination of military and non-military as well as covert and overt means, including disinformation, cyber attacks, economic pressure, deployment of irregular armed groups and use of regular forces”5 while the EU defined hybrid threats as those representing “mixture of coercive and subversive activity, conventional and nonconventional methods (i.e. diplomatic, military, economic, technological), which can be used in a coordinated manner by state or non-state actors to achieve specific objectives while remaining below the threshold of formally declared warfare.”6 Recently, the concept has been increasingly used to suggest non-military means such as disinformation campaigns and cyber attacks as hybrid threats has been widely associated with Russia’s warfare.

This evolution in its definition has led to a conceptual confusion and given rise to a quite number of critiques. Many scholars have questioned the various aspects of the concept of hybrid warfare and its applicability to Russia’s warfare in Ukraine.7 In the years following Hoffman’s postulation, the concept of hybrid warfare was frequently discussed in the context of irregular warfare,8 some analysts—including the British military—argued that it is just a subset of irregular warfare.9 In a report written by the United States Government Accountability Office (GAO) for the US House of Representatives in 2010, the GAO concluded that the DOD had not officially defined hybrid warfare at that time and has no plans to do so because the DOD does not consider it to represent a new form of warfare. For the majority of officials, the use of the term hybrid warfare describes the increasing complexity of future conflicts as well as the nature of the threats posed. According to the report, some officials see hybrid warfare as a potent, complex variation of irregular warfare while others do not use the term hybrid warfare, stating that current doctrine on traditional and irregular warfare is sufficient to describe the current and future operational environment.10 Colin S. Gray questions the added value of Hoffman’s conceptualisation, criticising Hoffman’s definition for being both too inclusive to be analytically useful, yet also too suggestive of some exclusivity (to warrant the hybrid badge at least) to accommodate the rich complexity of historical reality. He finds that the definition includes everything other than purely criminal or military behavior to the degree to which even these superficially distinctive activities are unambiguously distinguishable.11

In the aftermath of Russia’s annexation of Crimea, which is a period that the broader definition becomes dominant, it has been increasingly compared to the concepts such as political warfare or unconventional warfare. For instance, Michael Kofman and Matthew Rojansky argued that Russian approach to war is usually cited in Western military discourse under concepts of “unconventional” warfare and “political” warfare.12 Robert Johnson also suggests that what today might be deemed hybrid warfare was labelled as ‘political warfare’ during the Cold War.13 According to Mark Galeotti, given the methods used by Russia, it is more appropriate to talk about a “political war” rather than a hybrid war in the context of the current Russia-West relationship.14 Furthermore, as Élie Tenenbaum states, ‘hybrid warfare’ has transformed into a ‘strategic potluck’ where each member state or organization understood the term in their own way and ‘its meaning has been diluted to the point of absurdity, referring to matters as different as the rise of Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, drug-related violence in Mexico or the political strategy of Russia in Ukraine.’15 Few analysts have employed Hoffman’s actual concept, instead they have loosely referred to the hybridity, but usually implying different meanings.16

Against this background, this paper aims to measure the ambiguity of the concept of hybrid warfare and the impact of Russia’s invasion of Crimea on the evolution of the concept through the content analysis. To achieve this purpose, a content analysis was carried out on 230 media items that were released over a period between 01 January 2011 and 01 January 2017 in order to reveal the meanings attached to term “hybrid warfare” in each media item. The first section, which provides a brief explanation about the methodology and the data analysis, is followed by the second section that presents the definitions of all potential terms that are likely to be used interchangeably with hybrid warfare. The last two sections present the research findings and discusses their implications.

The Methodology, Sampling and Data Collection of Content Analysis

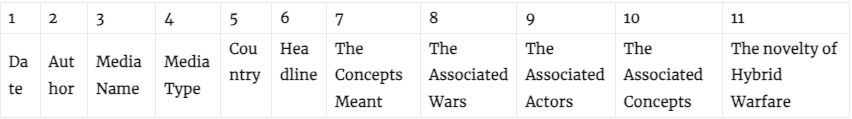

The content analysis refers to any technique for making inferences by objectively and systematically identifying specified characteristics of messages.17 It is an approach used to analyse documents and texts that seeks to quantify content in terms of predetermined categories and in a systematic and replicable manner.18 To ensure an objective and systematic study, a coding schedule which includes eleven predetermined categories, with each of the columns representing a category, has been developed. In other words, each media item is a coded for eleven categories that are displayed in Table 1. A coding book, which includes instructions to coders and all possible alternatives for each category also can be found in Appendix A.

Table 1-Coding schedule

One could argue that the seventh category is the most important category as it reveals the actual meaning of hybrid warfare and the changes in its meaning over time; hence it provides answers to the main research question of this paper. For this category, nine concepts which are likely to be used interchangeably with the concept of hybrid warfare were predetermined. Each media item was analysed in order to determine that the term hybrid warfare corresponds to which one of nine concepts that are explained in the following section. This provides an objective and systematic manner in order to understand what the authors really mean when they used the term hybrid warfare.

The categories from eight to eleven are used to enhance and contribute to the findings of the seventh category. If an author gives an example of hybrid war in the media item, it is entered into the eighth column. This provides some concrete examples about how different authors perceive the concept of hybrid warfare in practice. In the ninth column, the type of actor that employs hybrid warfare is noted. Although both Hoffman’s definition and the extended definition postulate that both state and non-state actors can employ hybrid warfare, most media items refer to one type of actor. This does not necessarily mean that the authors suggest that hybrid warfare is employed by only one type of actor, however their description of actor hints at their perceptions of the concept.

In the tenth category, similar concepts or synonyms that are used for hybrid warfare are entered. For instance, an author writes: “the terms fourth-generation warfare, hybrid warfare and unconventional warfare are often used simultaneously, but only unconventional warfare is a doctrinal term recognized by the Defence Department.” One may assume that these three terms are grouped together as they have similar characteristics. In another example, an author writes: “the government points to the risk of ‘hybrid warfare’ or ‘full spectrum conflict,’ i.e. a co-ordinated use of all possible tools.” One can understand that the author regards “hybrid warfare and full spectrum conflict” as synonyms. Hence, the concepts associated with hybrid warfare help us to better understand the perceptions of authors about the term hybrid warfare. Lastly, in the eleventh column, it is noted whenever an author modified hybrid warfare as a new type of warfare or clearly rejected the novelty of the concept. As the novelty of the concept is one of the main topics that the concept of hybrid warfare is criticized, this category also provides additional information about the perceptions of the authors on hybrid warfare.

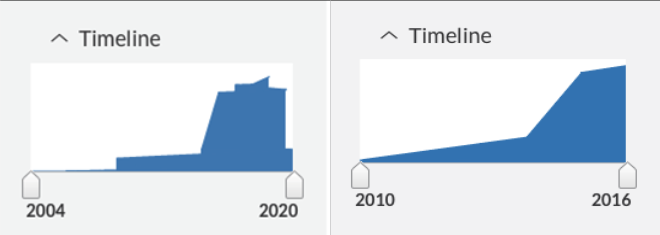

The data set was created by a search on the online media database “Lexis Nexis” for all type of news items including news transcripts, newswires & press releases, magazines & journals, newspapers, aggregate news sources, web-based publications, blogs, and video and audio transcripts published from 01 January 2011 to 01 January 2017. Since the second purpose of this study is to understand the impact of Russia’s invasion on the concept, this period which provides a sufficient amount of time both before and after Russia’s annexation of Crimea is deemed appropriate. “Hybrid warfare” as a search term was used in order to locate news items regarding the concept of hybrid warfare, and this search produced 4347 media items in total. The volume of media items significantly changes in 2014. As seen in Figure 1, there is a sharp increase in the number of media items in the months immediately following Russia’s annexation of Crimea.

Figure 1 The Change in the Volume of Media Items (received from Nexis Uni.)

In principle, probability sampling was employed given the high number of media items (4347 in total). A media item from Monday in the first week provided the first item included in analysis, followed by Tuesday in the following week, Wednesday the week after and so on. This method allowed to analyse one media item from each week belonging to different days of the week. In case a media item could not be found on a specific date sought; the media item dated closest to this specific date for that week was used for the analysis. However, since the volume of the media items heavily skewed towards the period after 2014, the number of media items before Russia’s annexation of Crimea did not allow for employing a probability sampling. For this reason, instead of sampling, all eligible media items between 01 January 2011 and 13 September 2014 were analysed. Only after 13 September 2014, which is the date when the number of media items started to increase significantly, the probability sampling was employed. To sum up, as shown in Figure 1, while all media items between 01 January 2011 and 13 September 2014 are analysed, a probability sampling is employed for the media items between 14 September 2014 and 01 January 2017.

Figure 2-Sampling of Content Analysis

In the first period, where the number of media items is low, the search item “hybrid warfare” yielded 472 media items. Once the duplications and useless items were eliminated, 106 media items remained to be analysed. Some items were useless because they did not include a sufficient amount of text to analyse, or they were not relevant for the predetermined categories. For the second period, the same search yielded 3876 media items. The probability sampling described above (one item per week belonging to different days) was employed and 124 media items were analysed. Before proceeding the definitions of concepts, it is important to note the one main limitation of this research. The news database that was used for the searches is not exhaustive although it covers a wide range of local and international news sources. In other words, it doesn’t represent whole universe of media items titled “hybrid warfare.”

The Definition of Terms/Concepts

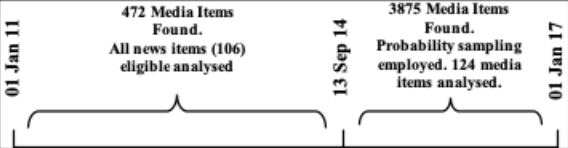

The critics argue that hybrid warfare is a broad and ambiguous concept which is why it is frequently used interchangeably with other terms such as comprehensive approach, political warfare, irregular warfare, unconventional warfare or information warfare, etc. A closer look at these terms reveals that there are significant overlaps in their meanings and definitions. To establish a common understanding, the definitions of the terms associated with hybrid warfare are presented in the following paragraphs. They are presented in three main groups which include closely related terms.

Hybrid Warfare-Comprehensive Approach-Political Warfare

A review of literature shows that the definition of hybrid warfare has expanded. While Hofmann’s definition posits a convergence of different types of warfare at the operational/tactical levels, it has become broader and incorporated non-military means into the definition particularly after Russia’s war in Ukraine. Therefore, two different labels were used in the coding, “hybrid warfare1” for its narrower meaning, and “hybrid warfare2” for its broader meaning. Any media item describing hybrid warfare as a combination of different modes of warfare, namely regular, irregular, terrorism or criminal activities at the operational/tactical levels, and as a warfare confined to the battlefield without referring to broader aspects is coded as “hybrid warfare1.” However, when it is described as a combination of military and non-military means, namely as the use of regular and irregular forces along with economic, political, diplomatic and informational tools, this item is coded as “hybrid warfare2.”

Comprehensive Approach was defined as “blending civilian and military tools and enforcing co-operation between government departments, not only for operations but more broadly to deal with many of the 21st century security challenges, including terrorism, genocide and proliferation of weapons and dangerous materials” in a report of the UK House of Commons Defence Committee.19 NATO suggests that “addressing crisis situations calls for a comprehensive approach combining political, civilian and military instruments. Military means, although essential, are not enough on their own to meet many complex challenges to our security.”20 As NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg stated in NATO’s Transformational Seminar, Russia’s hybrid warfare can be seen as a “dark reflection” of the comprehensive approach.21 According to this line of thought, the difference between comprehensive approach and hybrid warfare lies in the aim. Comprehensive approach aims to build or strengthen the governance, whereas hybrid warfare aims to weaken it. Otherwise, these terms are the same in their essence.

Political Warfare, in George Kennan’s definition, is the employment of all the means short of war at a nation’s command to achieve its national objectives in peacetime. Tools used in political warfare are non-kinetic in nature, whereas hybrid warfare connotes the combination of kinetic and non-kinetic military means.22 Political warfare includes all elements of national power: diplomatic, informational, military, and economic. However, differently from hybrid warfare, military tools have unconventional characteristics in political warfare, which is rather limited to the use of proxy forces, military aid to a state, etc. In this study, any media item is categorized as “political warfare” when the author described the use of unconventional military activities along with diplomatic, economic, informational measures rather than the combination of conventional and non-conventional activities.

Irregular Warfare-Unconventional Warfare-Subversive Warfare

Irregular Warfare refers to any violent struggle among state and non-state actors for legitimacy and influence over the relevant population. Irregular warfare favours indirect and asymmetric approaches, though it may employ the full range of military and other capabilities, in order to erode an adversary’s “power, influence, and will.”23 What makes irregular warfare different is the focus of its operations—a relevant population—and its strategic purpose: to gain or maintain control or influence over, and the support of, that relevant population.24 Irregular warfare includes: “any relevant activity and operation such as counter terrorism; unconventional warfare; foreign internal defence; counterinsurgency; and stability operations that, in the context of irregular warfare, involve establishing or re-establishing order in a fragile state or territory.”25 Another difference from hybrid warfare is that irregular warfare is limited to the wars between state and non-state actors while hybrid warfare can also be employed by a state to another state.

Unconventional Warfare refers to a broad spectrum of military and paramilitary operations, normally of long duration, predominantly conducted through, with, or by indigenous or surrogate forces that are organised, trained, equipped, supported, and directed to varying degrees by an external source. It includes, but is not limited to, guerrilla warfare, subversion, sabotage, intelligence activities, and unconventional assisted recovery.26 Unconventional Warfare is one of the five main activities identified under Irregular Warfare.27 It is composed of “activities that are conducted to enable a resistance movement or insurgency to coerce, disrupt, or overthrow a government or occupying power by operating through or with an underground, auxiliary, and guerrilla force in a denied area.”28

Subversive Warfare: According to the Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms, subversion is an “action designed to undermine the military, economic, psychological, or political strength or morale of a regime.” This is quite similar to the definition of unconventional warfare. It is noted in the same dictionary that “anyone lending aid, comfort, and moral support to individuals, groups, or organizations that advocate the overthrow of incumbent governments by force and violence is subversive and is engaged in subversive activity.”29

All three terms—irregular warfare, unconventional warfare, and subversive warfare—are quite similar concepts as they postulate the use of a broad spectrum of military and non-military capabilities by non-state actors to coerce, disrupt, or overthrow an established government. However, irregular warfare has the broadest meaning, and it represents the general notion of warfare between state and non-state actors. In addition to unconventional warfare, which posits the use of irregular forces to disrupt and overthrow an established government, irregular warfare is comprised of activities such as counterinsurgency and counterterrorism, which postulates an established government’s fight against irregular forces. However, unconventional warfare is particularly about the use of a resistant movement, an insurgency—although one may term it proxy forces by an external power. Similarly, unconventional warfare has a broader meaning than subversive warfare because it contains additional instruments such as guerrilla warfare, sabotage, intelligence activities, and unconventional assisted recovery. Subversive activities, as suggested in the Cambridge dictionary, connote the attempts to change or weaken a government by working secretly within it.30 It has the same aim as unconventional warfare, but with more subtle methods through undermining social and moral integrity.

Information Warfare-Psychological Operations-Propaganda

Information warfare is the conflict between two or more groups in the information environment.31 While there is no official definition of “information warfare” in U.S. military publications, the Joint Chiefs of Staff characterizes “information operations” as the integrated employment, during military operations, of information-related capabilities (IRCs) in concert with other lines of operation to influence, disrupt, corrupt, or usurp the decision making of adversaries and potential adversaries while protecting our own.32 Information warfare aims to use the information itself as the weapon. It is possible to use a broad range of tools to conduct information warfare, as it is inherently multidisciplinary and multidimensional. Cyber capabilities are just one of many tools used to carry out that task.

Cyber warfare has a more technical and narrower meaning and focuses on disrupting and disabling the computer and cyber systems themselves. It does not represent warfare alone but is rather a tool used in a broader warfare concept. In most articles, propaganda-psychological warfare or information warfare is used together with cyber warfare, because they are closely related. Since cyber warfare is only a tool in the realization of these concepts, throughout this study, the term will not be taken as a separate label for warfare.

Propaganda is defined as “any form of communication in support of national objectives designed to influence the opinions, emotions, attitudes, or behaviour of any group in order to benefit the sponsor, either directly or indirectly.”33 For Taylor, it is “the conscious, methodical and planned decisions to employ techniques of persuasion designed to achieve specific goals that are intended to benefit those organizing the process.” 34

Psychological Operations are those planned operations intended to convey selected information and indicators to foreign audiences in order to influence their emotions, motivations, objective reasoning, and ultimately the behaviour of foreign governments, organizations, groups, and individuals. The purpose of psychological operations is to induce or reinforce foreign attitudes and behaviour favourable to the originator’s objectives.35

As the definitions demonstrate, propaganda, psychological operations or information warfare are closely linked and there are no major differences among their definitions. In summary, all three concepts posit influencing the opinions, emotions, and motives of a target audience. For this reason, these terms are frequently used interchangeably. One can argue that information warfare has a rather broader meaning as it comprises also the use of information-related capabilities, even though the essence of the term is almost identical. For Tiina Seppala, information warfare has been termed “propaganda” long before it became known as “psychological warfare,” before then becoming known as “information warfare” due to the negative connotations the previous terms had.36 The increasing interdependency of communications systems with other infrastructures might be another reason for the use of the term “information warfare.” In any case, because of this close similarity in the meanings of the three concepts, “information warfare” will be used as the representative of this group of terms. Table 2 below depicts the comparison of the above-mentioned terms. To provide an easier understanding, they are compared based on several prominent characteristics of warfare.

All of the definitions have several overlapping aspects. To put it into a simpler frame, hybrid warfare is the most inclusive phenomenon of all the terms as it requires the simultaneous use of both military and non-military tools, by either state or non-state actors. Comprehensive approach has a very close meaning, which differs in the aim and the actor as it is used only by state actors. Political warfare connotes the use of all non-military tools with a limited use of military forces such as proxy forces and special forces while hybrid warfare postulates the simultaneous use of military and non-military tools. Irregular warfare is similar to hybrid warfare in that it includes the use of a broad range of military and non-military tools, but in a context where warfare is carried out between a state and a non-state actor. Unconventional warfare is a part of irregular warfare but has a narrower meaning as it particularly represents the use of military—irregular forces against an established government. Subversive warfare is similar to unconventional warfare; however, the tools used in subversive warfare are more subtle and limited. Information warfare, propaganda and psychological warfare use the information as a weapon itself with the main purpose being to influence the perception of the relevant population. They are not the concept of warfare themselves but usually employed as part of other operational concepts.

A Note on the Attribution of Concepts

A brief explanation about the coding process of the media items and particularly the “the concepts meant” category would be helpful to illuminate the conduct of the content analysis that is used in this study. One of the biggest challenges during the coding process was distinguishing between “hybrid warfare” and “political warfare” or between “political warfare” and “unconventional warfare” as their definitions overlap significantly. Hybrid warfare is

Table 2-The Comparison of various concepts

frequently mistaken for political warfare, which is described as “the use of all instruments short of war, including military ones.” However, military capabilities in political warfare are unconventional in nature whereas hybrid warfare posits a combination of conventional and unconventional forces. Secondly, hybrid warfare is a phenomenon that has been coined to be employed in war whereas political warfare includes activities to be conducted in peacetime. In the Russia-Ukraine conflict, which is almost unanimously admitted being a model for hybrid warfare, Russia stationed its conventional forces at the border, ready to invade Ukraine while it had pro-Russian proxy forces in Ukraine as well. At a certain point, Russia even had to use its conventional fire-support against Ukrainian forces. This was more than the use of military in political warfare, which is limited to supporting proxy forces or organizing resistance groups along with the use of national powers. This slight difference between the two terms has been taken into consideration. Media items which imply the use of all instruments short of war, including non-kinetic military units, are coded as “political warfare” unless they suggest a combination of military and non-military tools.

For instance, in a report by the Ministry of Defence of the Kingdom of Sweden, hybrid warfare is described as the following:

The Russian aggression and its operations in and outside of Ukraine follow a pattern of a “Hybrid Warfare.” Power is being projected simultaneously in all domains by a mix of state and non-state actors in a clearly coordinated fashion and seemingly with clear and determined goals. This Hybrid warfare is made possible by the fact that there is a clear and credible conventional, as well as nuclear, military capability underlining Russian actions… More importantly, Russia has shown a willingness to use military means alongside other tools to achieve her goals. (emphasis added)37

This description corresponds to the extended definition of hybrid warfare and this media item is coded as “hybrid warfare2” because it includes the use of both conventional and non-conventional military forces in addition to other non-military tools. In another media item which includes a speech of Alexander Vershbow, NATO Deputy Secretary General, he describes hybrid warfare as the following:

Russia has resorted to a new type of “hybrid warfare” that combines military intimidation, covert supply of weapons and fighters, economic blackmail, diplomatic duplicity, media manipulation, and outright disinformation. It may be withdrawing its regular troops from the Ukrainian border, but its aggressive behavior has not diminished and it continues to destabilise Ukraine in different ways. (emphasis added)38

In this description, Vershbow also indicates the use of all national powers, however the military is used for “intimidation,” for rather the covert use of proxy forces. This is why this media item is coded as “political warfare.”

In the same vein, the difference between “political warfare” and “unconventional warfare” also requires a particular attention. Comparing the definitions of the two concepts, one can deduce that unconventional warfare is only one component of political warfare.39 Unconventional warfare consists of only those “activities conducted to enable a resistance movement or insurgency to coerce, disrupt, or overthrow a government or occupying power by operating through or with an underground, auxiliary, and guerrilla force in a denied area.” This definition actually corresponds to the military dimension of political warfare, which postulates the use of a proxy force in another country. Here is a description from a televised news report:

The head of NATO said today he is in no doubt that Russia is conducting a secret military operation to destabilise eastern Ukraine, calling it a kind of hybrid warfare involving undercover forces. Ukraine’s government is still fighting to regain towns and cities in the East from separatists. (emphasis added)40

This item solely describes the military dimension of political warfare as it posits the secret use of proxy forces to destabilise eastern Ukraine, which is tantamount to the definition of unconventional warfare. Therefore, this media item is coded as “unconventional warfare.”

In some articles, the author clearly states what they meant by their use of the term hybrid warfare, so no interpretation is required in such cases. For instance, Paul J. Saunders, states that “the term applied to Russia’s particular approach to irregular warfare in Ukraine is the threat du jour in international security affairs,” and he maintained, “nevertheless, since we might see more such irregular warfare in the future, we should insist on greater precision and honesty in our conversations.”41 (emphasis added) In such cases where the authors clearly used the type of warfare that they associated with hybrid warfare, it is directly entered without further analysis. Therefore, Saunders’s article was coded as “irregular warfare” as he clearly writes that hybrid warfare is a type of irregular warfare.

Research Findings and Discussion

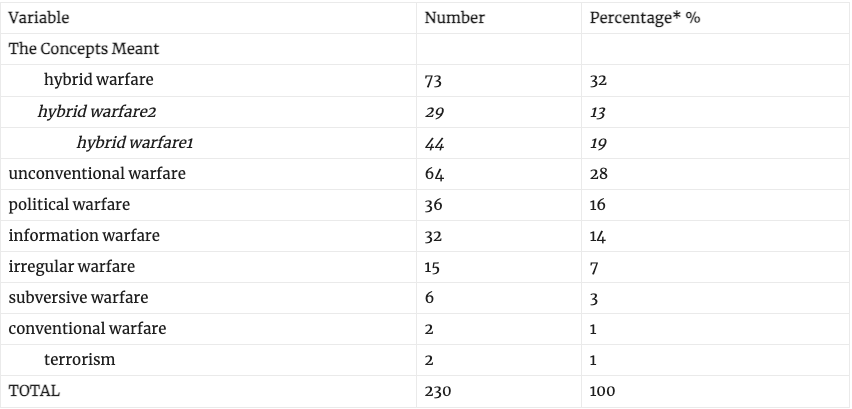

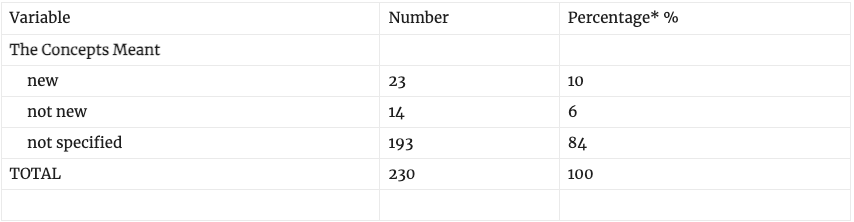

Based on the criteria explained above, 230 media items that were released over the 2011-2017 period have been analysed. In this section, the research findings starting from the seventh category, namely “The concepts meant” by hybrid warfare category, will be presented. Table 3 displays the results regarding this category.

Table 3-Results for the “The Concepts Meant” Category

* The numbers are rounded to the nearest integer.

The results demonstrate that the term “hybrid warfare” is used in accordance with its definition in 73 (32%) media items. In other items, the authors describe another concept when they use the term “hybrid warfare.” For instance, they describe “unconventional warfare” in 64 (28%) items, “political warfare” in 36 (16%) items, “information warfare” in 32 (14%) items, “irregular warfare” in 15 (7%) items, “subversive warfare” in 6 (3%) items and “conventional warfare” in 2 (1%) items. These results clearly demonstrate that hybrid warfare is an ambiguous concept and there is no common understanding of hybrid warfare in the media items. Most of the time (68%), the authors are describing another concept when they use the term hybrid warfare.

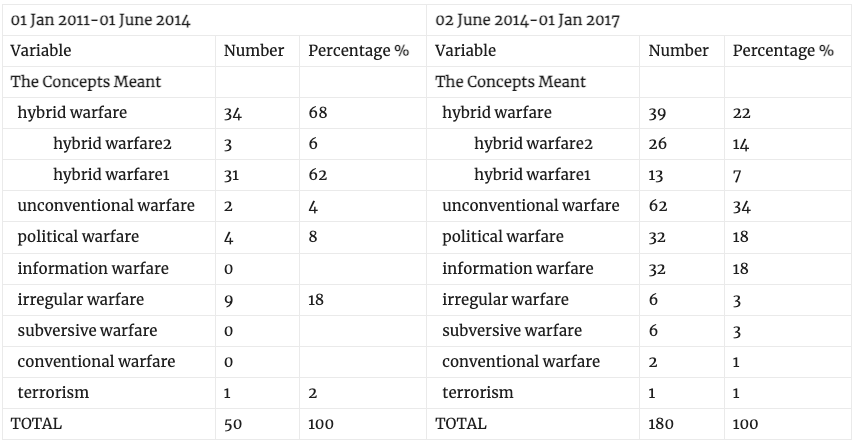

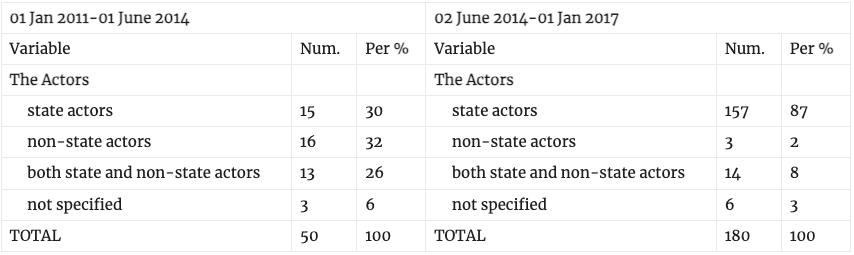

As mentioned before, another purpose of this chapter is to explore the changes in the meaning of hybrid warfare in relations with Russia’s annexation of Crimea. As depicted in Table 4, the results are divided by a specific date, 01 June 2014, which allows to see the impact of Russia’s invasion. Considering that Russia completed its invasion of Crimea at the end of March in 2014 and it took some time for the Western world to associate the concept of hybrid warfare with Russia’s warfare in Crimea, the beginning of June 2014 is thought of as a reasonable separation date.

Table 4-The Impact of Russia’s Annexation of Crimea

Table 4 suggests three important themes. First of all, these results confirm that the definition of hybrid warfare expanded following Russia’s invasion of Crimea. While only three authors describe the concept in a broad version (hybrid warfare2), the majority of the authors [31 (62%)] use the narrow definition (hybrid warfare1) before June 2014, with the number of broad version users increasing to 26 (14%) after June 2014. In other words, in the aftermath of Russia’s invasion of Crimea, the concept of hybrid warfare was used in its broad meaning rather than the narrow one. (26/39-13/39)

Secondly, not only the definition of the concept has expanded but also the ambiguity around the concept has dramatically increased following Russia’s invasion of Crimea. While there was a relatively common understanding of the concept in the first period—as the majority of the authors used the term in accordance with Hoffman’s definition [31 (62%)] and partially in accordance with irregular warfare [9 (18%)], the number and the variety of concepts ascribed to the term considerably increased in the second period. In the aftermath of Russia’s annexation, only in 39 (22%) out of the 180 media items was the concept used in its actual definition. Although the authors used the term “hybrid warfare,” they described “unconventional warfare” in 62 (34%) items, “political warfare” in 32 (18%) items and “information warfare” in 32 (18%) items.

These findings might further indicate that the use of the term is closely linked to the international context. For instance, hybrid warfare was used as a synonym for information warfare starting from the beginning of 2015, but particularly during 2016 when Russia’s intervention in the elections of US and Europe was widely discussed. It is likely that the use of the term as a synonym for information warfare would continue at an increasing rate in the following years if the period analysed would be further extended. While one reason for the loose use of the term might be the broad definition of the concept, another reason might be the tendency to associate the term with the changes in the international context.

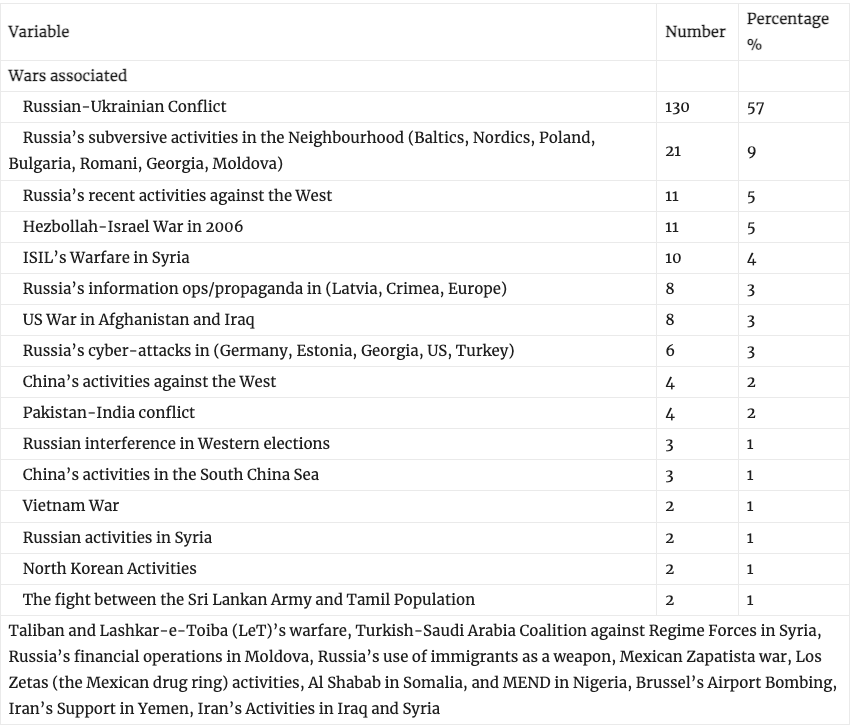

Another coding category is the wars that were associated with hybrid warfare. Some authors provided examples of wars where hybrid warfare was employed. Table 5 on the next page provides a list of wars that are associated with hybrid warfare in this research. One interesting finding in this table is that more than half of the authors regard the Russia-Ukraine Conflict (57%) as the preeminent example of hybrid warfare. Furthermore, two other examples, “Russia’s subversive activities in the Neighbourhood” and “Russia’s recent activities against the West” are also closely related to Russia’s activities. This finding verifies that the Russian-Ukraine Conflict is perceived as a model for hybrid warfare by the international community.

A closer look at the media items highlights that oftentimes the Russia-Ukraine Conflict is the only example that is discussed in reference to hybrid warfare. In other words, most of the time, the concept of hybrid warfare is discussed in the context of the Russia-Ukraine Conflict. This also signals the magnitude of the impact of Russia’s warfare in Crimea and Eastern Ukraine on the Western community. It suggests that the shock surrounding Russia’s invasion created such an atmosphere in the West that many analysts have chosen a relatively new phenomenon to describe it.

Another important finding is the diversity of the wars that are associated with hybrid warfare. On the one hand, classic coercive-deterrence strategies between two states such as Pakistan-India or between Russia-NATO, on the other hand, the insurgencies that are carried out by non-state actors such as the Taliban or ISIL are labelled by hybrid warfare. Furthermore, even extreme examples such as “Russia’s alleged financial fraud in Moldova’s bank” or

Table 5-The Wars Associated with Hybrid Warfare

“Mexican drug gang Los Zetas’ activities” can be associated with hybrid warfare. While this can be interpreted as the insufficient information that analysts have about hybrid warfare; it can also signal the ambiguity of the concept as it allows such a wide coverage.

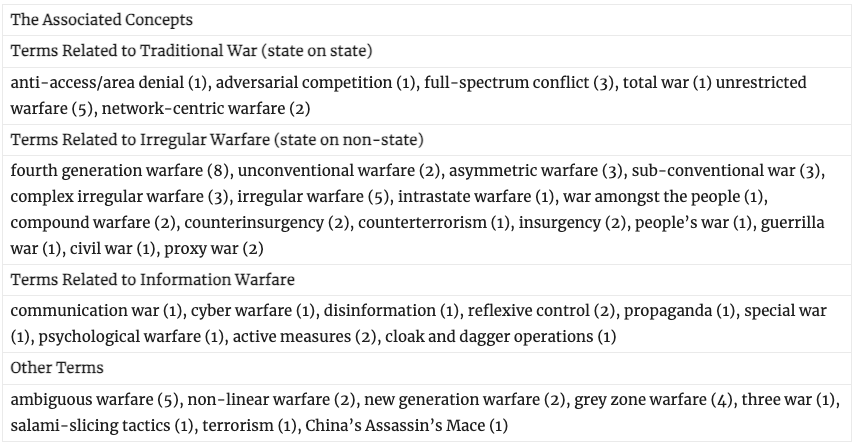

Some authors use synonyms for the concept of hybrid warfare. While in some media items, the authors used an exact synonym for hybrid warfare, in other items they used other concept/concepts to show close similarity between them. Both kinds of concepts that were used by authors are displayed in Table 6. Similar to the wars associated with hybrid warfare, the findings in Table 6 signal one important theme; the concepts associated with hybrid warfare are also incredibly diverse. The authors used different concepts ranging from traditional warfare concepts such as “total war” to information warfare concepts such as “propaganda.” This diversity also indicates how ambiguous its definition is.

Table 6– The Concepts Associated with Hybrid Warfare

According to the definition of hybrid warfare, it can be used by both state and non-state actors. The actors involved in warfare are important in the sense that they give us an idea about the type of warfare. For instance, it is less likely for a non-state actor to employ a conventional war, or it is less likely for a state actor to conduct an insurgency. Although the concept of hybrid warfare postulates both state and non-state actors, the initial perception among the defence community was closer to the idea that non-state actors use the concept. Hoffman also regarded Hezbollah’s tactics against Israel as the first clear example of hybrid warfare. However, the attribution of hybrid warfare to Russia’s annexation of Crimea has changed this perception. Following Russia’s invasion, most authors have discussed hybrid warfare as a concept that is used by state actors. The findings in Table 7 demonstrate this change of perception. While non-state actors were thought of as the primary users of hybrid warfare before Russia’s annexation of Crimea, the majority of authors regarded hybrid warfare as a concept that is used by state actors after Russia’s annexation.

Table 7-The Actors that use Hybrid Warfare

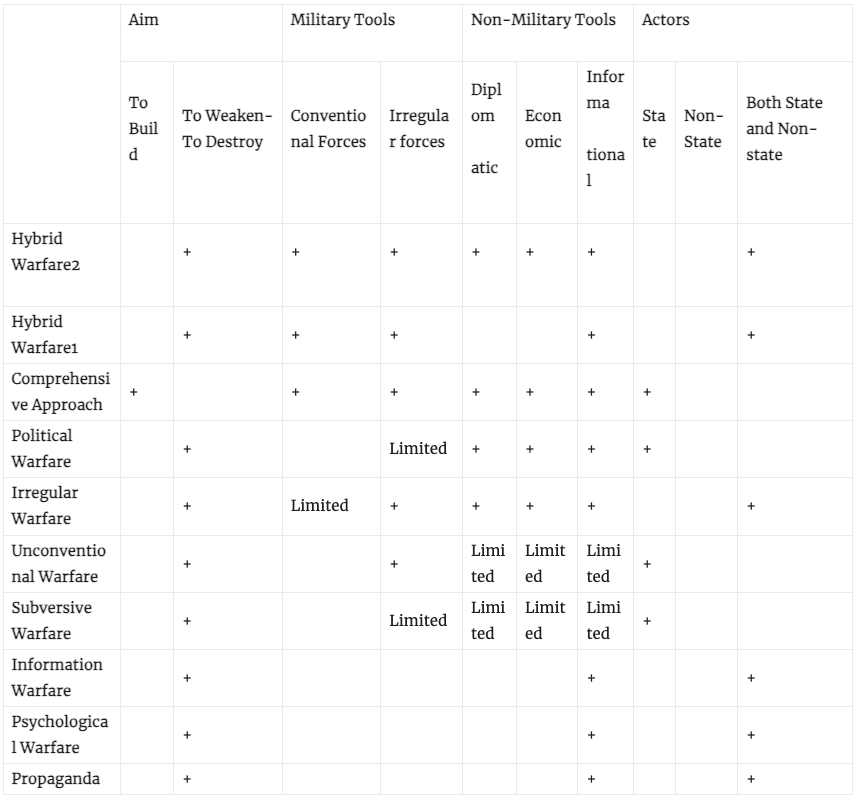

Finally, all of the media items were examined to assess whether the author considers hybrid warfare as a new type of warfare or not. The findings of this category (Table 8) do not provide a meaningful data to understand the perceptions of the authors on this issue because the majority of the authors (84%) did not specify any ideas about the novelty of the concept. However, one can argue that there is a tendency to see hybrid warfare as a new type of warfare as 10% of the authors claim that the concept of hybrid warfare is new whereas 6% of the authors reject this idea.

Table 8 The Novelty of the Concept of Hybrid Warfare

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that hybrid warfare is an ambiguous term. The authors suggest a different concept 68% of the time while they are using the term hybrid warfare. The diversity of the wars and concepts that are associated with hybrid warfare in the media items also confirms the ambiguity of the concept. The wars ranging from the “Vietnam War” to “Russia’s use of immigration as a weapon”, or the concepts ranging from the “anti-access/area denial” to “salami-slicing tactics” can be labelled as hybrid warfare. A similar diversity applies to the actors that employ the concept of hybrid warfare. While non-state actors were usually perceived as the main actors who employed hybrid warfare before Russia’s annexation of Crimea, state actors have become the primary actors in the period following Russia’s invasion. While this study covers the period between 2011-2017, the critiques around the ambiguity of the concept appears to have remained to date. For instance, Vladimir Rauta has recently argued that the academic debate has reached a consensus that the notion of “hybrid war/warfare” has to be approached cautiously. It is now known as a conceptual trap.42

As Hew Strachan noted, “words convey concepts: if they are not defined, the thinking about them cannot be clear… Such ambiguity creates confusion within individual nations, let alone alliances ostensibly speaking a common language”43 Indeed, as words convey concepts, concepts shape our understanding of defence, and thus our armed forces, doctrines and the way that armed forces fight. Despite the heated debates around the concept, it is widely used in the Western defence community. Both NATO and the EU use the term in their strategic documents and develop comprehensive strategies against hybrid threats which lead to a tangible increase in terms of capability building and defence budgets. However, this may carry the risk of spending money on the wrong things given the ambiguity over the concept of hybrid warfare. This also raises the question as to how policy and strategy makers would have a sound discussion about current warfare if they cannot agree upon the concept. It is therefore important to have an agreed definition/description before adopting a concept which leads to consequences.

Another important aspect that emerges out of this study is the fact that the meaning of concept has been very much affected by the international context. There is a notable evolution in the definition of the concept in terms of actors, types and levels of warfare depending on the major international events. While hybrid warfare was understood as a type of warfare conducted by mainly non-state actors at the operational/tactical levels, it has evolved to a type of warfare conducted by mainly state actors at the political/strategic levels even though it simply represented the modern warfare in both periods. When the term was first coined in the beginning of 2000s, the US and the Western world was occupied with addressing the global terrorist network of Al-Qaida which committed 9/11 terrorist attacks and insurgencies in Iraq and Afghanistan. So, major threat was non-state actors. This was changed first by Russia’s invasion of Crimea, but also by China’s increasing hostile behaviour and Iran’s increasing influence in Iraq and Syria. The threat du jour has changed to the state actors. However, the term hybrid warfare has continued to be used to describe contemporary threats.

Chris Tuck attributes this problem to the generalizing from the specific. According to Tuck, first “Hoffman generalised about hybrid war from the specifics of the armed conflict between Israel and Hezbollah in 2006; McCuen generalised from the specific state-building conflicts of Iraq and Afghanistan; and more recently, hybrid war has been generalised as a phenomenon from the specifics of Russian activities in Crimea and the Donbas. Hybrid war seems to be redefined in relation to the characteristics of each new conflict that worries the West.”44 This can also be explained by what Colin S. Gray names “presentism.” According to Gray, there is a tendency among people to perceive the current problems as unique and a failure to observe historical continuities. People have enormous difficulty transcending the paradigm, current opinions and assumptions of today.45

Last but not least, it is important to note that one should be cautious in using new terms in order to describe contemporary warfare. As Gray noted, most of new strategic theories or innovative doctrines presented as a radical change from preceding behaviour is readily locatable in the ever-contestable historical record. For instance, the enemy in Vietnam War posed nothing if not hybrid threats in complex conflicts, or comprehensive approach, which was coined by the British has long been known by another name, grand strategy.46 Indeed, as this study showed, numerous concepts posit the same notion even though they have different names and there are significant overlaps between different concepts. While concepts are useful in order to understand the characteristics of distinct the types of warfare, it is important to know that they are intellectual constructs of our choice, reality does not dictate them.47 Too much focus on conceptualisation might lead to the inability to see the forest for the trees, hence lose the strategic thinking.

Bibliography

Angstrom, Jan. ‘Escalation, Emulation, and the Failure of Hybrid Warfare in Afghanistan’. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 0731, no. February (2016): 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2016.1248665.

Bartles, C. ‘Getting Gerasimov Right’. Military Review, no. January-February (2016): 30–38.

Bryman, Alan. Social Research Methods. 4th Editio. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Cambridge Dictionary. ‘“Subversion”’. Accessed 15 June 2020. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/subversion.

Charap, Samuel. ‘The Ghost of Hybrid War’. Survival 57, no. 6 (2015): 51–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2015.1116147.

Chivvis, Christopher S. ‘Understanding Russian “Hybrid Warfare” And What Can Be Done About It’. 2017.

Department of Defense. Irregular Warfare (IW) Joint Operating Concept (JOC). Department of Defense, 2007. https://fas.org/irp/doddir/dod/iw-joc.pdf.

———. Joint Publication 1-02 Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms, 2001.

Department of Defense Directive 3000.07. Irregular Warfare. U.S. Department of Defense, 2014. https://fas.org/irp/doddir/dod/d3000_07.pdf.

Enstrm, Karin. ‘Military Thinking in the 21st Century,Newswire, May 15, 2014 Thursday’. State News Service, 2014.

European Commission. ‘Joint Framework on Countering Hybrid Threats a European Union Response’, 2016.

Fridman, Ofer. ‘Hybrid Warfare or Gibridnaya Voyna?: Similar, but Different’. RUSI Journal 162, no. 1 (2017): 42–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/03071847.2016.1253370.

Galeotti, Mark. ‘Hybrid, Ambiguous, and Non-Linear? How New Is Russia’s “New Way of War”?’ Small Wars & Insurgencies 27, no. 2 (2016): 282–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/09592318.2015.1129170.

———. Russian Political War: Moving beyond the Hybrid Account. Routledge, 2019.

Giles, Keir. ‘Russia ’s “ New ” Tools for Confronting the West Continuity and Innovation in Moscow ’s Exercise of Power’. Russia and Eurasia Programme, 2016.

Glenn, Russell W. ‘Thoughts on “ Hybrid ” Conflict’ 31, no. April 2008 (2009): 107–13.

Gray, Colin S. Categorical Confusion? The Strategic Implications of Recognizing Challenges Either As Irregular or Traditional. Carlisle PA: Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College, 2012.

———. ‘Coping With Uncertainty: Dilemmas of Defense Planning’. Comparative Strategy 27, no. 4 (2008): 324–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/01495930802358414.

———. The Strategy Bridge: Theory for Practice. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199579662.001.0001.

Hoffman, Frank G. ‘Conflict in the 21 St Century : The Rise of Hybrid Wars’. Potomac Institute for Policy Studies, 2007. http://www.potomacinstitute.org/.

———. ‘Further Thoughts on Hybrid Threats’. Small Wars Journal, 2009, 1–4.

———. ‘Future Threats and Strategic Thinking’. Infinity Journal Fall, no. 4 (2011): 17–21.

———. ‘Hybrid Threats : Reconceptualizing the Evolving Character of Modern Conflict’. Strategic Forum April, no. 240 (2009): 1–8.

———. ‘“Hybrid Threats”: Neither Omnipotent Nor Unbeatable’. Orbis 54, no. 3 (2010): 441–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orbis.2010.04.009.

———. ‘Hybrid vs. Compound War, The Janus Choice: Defining Today’s Multifaceted Conflicts’. Armed Forces Journal, no. October (2009).

———. ‘Hybrid Warfare and Challenges’. Joint Force Quarterly 1st quarte, no. 52 (2009): 34–39.

———. ‘On Not-So-New Warfare: Political Warfare Vs Hybrid Threats’. War on the Rocks, 2014, 1–4.

———. ‘Thinking About Future Conflict’. Marine Corps Gazette 98, no. 11 (2014): 10–19.

Holsti, O. R. Content Analysis for the Social Sciences and Humanities. Reading: MA: Addison-Wesley, 1969.

‘Inside Asprey: Luxury by Royal Appointment – 9:10 PM GMT-July 3, 2014 Thursday’. TVEyes – ITV 1 London, n.d.

Johnson, Robert. ‘Hybrid War and Its Countermeasures: A Critique of the Literature’. Small Wars and Insurgencies 29, no. 1 (2018): 141–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/09592318.2018.1404770.

Kofman, By Michael, and Matthew Rojansky. ‘A Closer Look at Russia’s “ Hybrid War ”’. Kennan Cable, 2015.

Kofman, Michael. ‘Russian Hybrid Warfare and Other Dark Arts’. War on the Rocks, 2016, 1–9. http://warontherocks.com/2016/03/russian-hybrid-warfare-and-other-dark-arts/.

Lanoszka, Alexander. ‘Russian Hybrid Warfare and Extended Deterrence in Eastern Europe’. International Affairs 92, no. 1 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2346.12509.

Libiseller, Chiara, and Lukas Milevski. ‘War and Peace: Reaffirming the Distinction’. Survival 63, no. 1 (2021): 101–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2021.1881256.

Livermore, Doug. ‘It’s Time for Special Operations to Dump Unconventional Warfare’. War on the Rocks, 2017.

Mattis, James N., and Frank Hoffman. ‘Future Warfare: The Rise of Hybrid Wars’. U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings Magazine 131, no. 11 (2005): 18–19.

McCuen, John J. ‘Hybrid Wars’. Military Review, no. April (2008): 107–13. http://www.au.af.mil/au/awc/awcgate/milreview/mccuen08marapr.pdf.

Mcculloh, Timothy, and Richard Johnson. ‘Hybrid Warfare’. Jboint Special Operations University. Florida, 2013. https://jsou.libguides.com/ld.php?content_id=2876897.

McWilliams, Sean J. ‘Hybrid War Beyond Lebanon: Lessons from the South African Campaign 1976 to 1989’. U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, 2009.

Monaghan, Andrew. ‘The “War” in Russia’s “Hybrid Warfare”’. Parameters 45, no. 4 (2016): 65–74.

NATO. ‘A “‘comprehensive Approach’” to Crises’. NATO Website, 2018.

———. ‘Keynote Speech by NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg at the Opening of the NATO Transformation Seminar’. NATO Website, 2015. https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/opinions_118435.htm.

———. ‘NATO’s Response to Hybrid Threats’, 2019. https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_156338.htm.

Nemeth, William J. ‘Future War and Chechnya: A Case for Hybrid Warfare’. Naval Postgraduate School, 2002. https://calhoun.nps.edu/bitstream/handle/10945/5865/02Jun_Nemeth.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

Popescu, Nicu. ‘Hybrid Tactics : Russia and the West’, no. October (2015): 2014–15. https://doi.org/10.2815/28861.

Porche III, Isaac R., Christopher Paul, Michael York, Chad C. Serena, Jerry M. Sollinger, Elliot Axelband, Endy Y. Min, and Bruce J. Held. Redefining Information Warfare Boundaries for an Army in a Wireless World. RAND Corporation, 2013.

Raitasalo, Jyri. ‘Hybrid Warfare : Where ’ s the Beef?’ War On The Rocks, 2015, 1–5. http://warontherocks.com/2015/04/hybrid-warfare-wheres-the-beef/.

Rauta, Vladimir. ‘Towards a Typology of Non-State Actors in “Hybrid Warfare”: Proxy, Auxiliary, Surrogate and Affiliated Forces’. Cambridge Review of International Affairs 33, no. 6 (2020): 868–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/09557571.2019.1656600.

Renz, Bettina. ‘Russia and “Hybrid Warfare”’. Contemporary Politics 22, no. 3 (2016): 283–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569775.2016.1201316.

Renz, Bettina, and Hanna Smith. ‘Russia and Hybrid Warfare – Going beyond the Label’. Aleksanteri Papers, 2016. www.helsinki.fi/aleksanteri/english/publications/aleksanteri_papers.html.

Robinson, Linda, Todd C Helmus, Raphael S Cohen, Alireza Nader, Andrew Radin, Madeline Magnuson, and Katya Migacheva. Modern Political Warfare: Current Practices and Possible Responses. RAND Corporation, 2018. https://doi.org/10.7249/RR1772.

Saunders, Paul J. ‘Why America Can’t Stop Russia’s Hybrid Warfare’. The National Interest, June 2015. https://nationalinterest.org/feature/why-america-cant-stop-russias-hybrid-warfare-13166.

Schroefl, Josef, and Stuart J. Kaufman. ‘Hybrid Actors, Tactical Variety: Rethinking Asymmetric and Hybrid War’. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 37, no. 10 (2014): 862–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2014.941435.

Seely, Robert. ‘Defining Contemporary Russian Warfare Beyond the Hybrid Headline’. RUSI Journal 162, no. 1 (2017): 50–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/03071847.2017.1301634.

Seppälä, Tiina. ‘“New Wars“ and Old Strategies: From Traditional Propaganda to Information Warfare and Psychological Operations’. In 23 Conference and General Assembly IAMCR/AIECS/AIERI International Association for Media and Communication Research, Barcelona,. Barcelona, 2002.

Strachan, Hew. The Direction of War: Contemporary Strategy in Historical Perspective. Cambridge University Press, 2013.

Suchkov, Maxim A. ‘Whose Hybrid Warfare? How “the Hybrid Warfare” Concept Shapes Russian Discourse, Military, and Political Practice’. Small Wars and Insurgencies, 2021, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/09592318.2021.1887434.

Taylor, Philip M. Munitions of the Mind. A History of Propaganda from the Ancient World to the Present Era. Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press, 1995.

Tenenbaum, Élie. ‘Hybrid Warfare in the Strategic Spectrum: An Historical Assessment’. In NATO’s Response to Hybrid Threats, edited by Guillaume Lasconjarias and Jeffrey A. Larsen. Rome: NATO Defence College, 2015.

Treverton, G. F., A. Thvedt, A. R. Chen, K. Lee, and M. Mccue. Addressing Hybrid Threats, 2018. https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1219292/FULLTEXT01.pdf.

Tuck, Chris. ‘Hybrid War : The Perfect Enemy’, 2017. https://defenceindepth.co/2017/04/25/hybrid-war-the-perfect-enemy/.

U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff. JP 3-13 Information Operations. U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, 2014. https://fas.org/irp/doddir/dod/jp3_13.pdf.

UK House of Commons Defence Committee. ‘The Comprehensive Approach: The Point of War Is Not Just to Win but to Make a Better Peace’. HC 224, Seventh Report of Session 2009–10, 2010.

United States Government Accountability Office. ‘Hybrid Warfare Report’. Washington, 2010.

US Joint Chiefs of Staff. ‘Joint Publication 3-05 Doctrine for Joint Special Operations’, no. July (2014). https://www.jcs.mil/Portals/36/Documents/Doctrine/pubs/jp3_05.pdf.

Vershbow, Alexander. ‘Remarks by NATO Deputy Secretary General at the SDA Conference: Overhauling Transatlantic Security Thinking- Newswire, June 4, 2014 Wednesday’. States News Service, 2014.

Walker, Robert G. ‘SPEC FI: The United States Marine Corps and Special Operations’. Naval Postgraduate School, 1998. https://calhoun.nps.edu/bitstream/handle/10945/8989/specfiunitedstat00walk.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

Angstrom, Jan. ‘Escalation, Emulation, and the Failure of Hybrid Warfare in Afghanistan’. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 0731, no. February (2016): 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2016.1248665.

Bartles, C. ‘Getting Gerasimov Right’. Military Review, no. January-February (2016): 30–38.

Bryman, Alan. Social Research Methods. 4th Editio. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Cambridge Dictionary. ‘“Subversion”’. Accessed 15 June 2020. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/subversion.

Charap, Samuel. ‘The Ghost of Hybrid War’. Survival 57, no. 6 (2015): 51–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2015.1116147.

Chivvis, Christopher S. ‘Understanding Russian “Hybrid Warfare” And What Can Be Done About It’. 2017.

Department of Defense. Irregular Warfare (IW) Joint Operating Concept (JOC). Department of Defense, 2007. https://fas.org/irp/doddir/dod/iw-joc.pdf.

———. Joint Publication 1-02 Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms, 2001.

Department of Defense Directive 3000.07. Irregular Warfare. U.S. Department of Defense, 2014. https://fas.org/irp/doddir/dod/d3000_07.pdf.

Enstrm, Karin. ‘Military Thinking in the 21st Century,Newswire, May 15, 2014 Thursday’. State News Service, 2014.

European Commission. ‘Joint Framework on Countering Hybrid Threats a European Union Response’, 2016.

Fridman, Ofer. ‘Hybrid Warfare or Gibridnaya Voyna?: Similar, but Different’. RUSI Journal 162, no. 1 (2017): 42–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/03071847.2016.1253370.

Galeotti, Mark. ‘Hybrid, Ambiguous, and Non-Linear? How New Is Russia’s “New Way of War”?’ Small Wars & Insurgencies 27, no. 2 (2016): 282–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/09592318.2015.1129170.

———. Russian Political War: Moving beyond the Hybrid Account. Routledge, 2019.

Giles, Keir. ‘Russia ’s “ New ” Tools for Confronting the West Continuity and Innovation in Moscow ’s Exercise of Power’. Russia and Eurasia Programme, 2016.

Glenn, Russell W. ‘Thoughts on “ Hybrid ” Conflict’ 31, no. April 2008 (2009): 107–13.

Gray, Colin S. Categorical Confusion? The Strategic Implications of Recognizing Challenges Either As Irregular or Traditional. Carlisle PA: Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College, 2012.

———. ‘Coping With Uncertainty: Dilemmas of Defense Planning’. Comparative Strategy 27, no. 4 (2008): 324–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/01495930802358414.

———. The Strategy Bridge: Theory for Practice. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199579662.001.0001.

Hoffman, Frank G. ‘Conflict in the 21 St Century : The Rise of Hybrid Wars’. Potomac Institute for Policy Studies, 2007. http://www.potomacinstitute.org/.

———. ‘Further Thoughts on Hybrid Threats’. Small Wars Journal, 2009, 1–4.

———. ‘Future Threats and Strategic Thinking’. Infinity Journal Fall, no. 4 (2011): 17–21.

———. ‘Hybrid Threats : Reconceptualizing the Evolving Character of Modern Conflict’. Strategic Forum April, no. 240 (2009): 1–8.

———. ‘“Hybrid Threats”: Neither Omnipotent Nor Unbeatable’. Orbis 54, no. 3 (2010): 441–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orbis.2010.04.009.

———. ‘Hybrid vs. Compound War, The Janus Choice: Defining Today’s Multifaceted Conflicts’. Armed Forces Journal, no. October (2009).

———. ‘Hybrid Warfare and Challenges’. Joint Force Quarterly 1st quarte, no. 52 (2009): 34–39.

———. ‘On Not-So-New Warfare: Political Warfare Vs Hybrid Threats’. War on the Rocks, 2014, 1–4.

———. ‘Thinking About Future Conflict’. Marine Corps Gazette 98, no. 11 (2014): 10–19.

Holsti, O. R. Content Analysis for the Social Sciences and Humanities. Reading: MA: Addison-Wesley, 1969.

‘Inside Asprey: Luxury by Royal Appointment – 9:10 PM GMT-July 3, 2014 Thursday’. TVEyes – ITV 1 London, n.d.

Johnson, Robert. ‘Hybrid War and Its Countermeasures: A Critique of the Literature’. Small Wars and Insurgencies 29, no. 1 (2018): 141–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/09592318.2018.1404770.

Kofman, By Michael, and Matthew Rojansky. ‘A Closer Look at Russia’s “ Hybrid War ”’. Kennan Cable, 2015.

Kofman, Michael. ‘Russian Hybrid Warfare and Other Dark Arts’. War on the Rocks, 2016, 1–9. http://warontherocks.com/2016/03/russian-hybrid-warfare-and-other-dark-arts/.

Lanoszka, Alexander. ‘Russian Hybrid Warfare and Extended Deterrence in Eastern Europe’. International Affairs 92, no. 1 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2346.12509.

Libiseller, Chiara, and Lukas Milevski. ‘War and Peace: Reaffirming the Distinction’. Survival 63, no. 1 (2021): 101–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2021.1881256.

Livermore, Doug. ‘It’s Time for Special Operations to Dump Unconventional Warfare’. War on the Rocks, 2017.

Mattis, James N., and Frank Hoffman. ‘Future Warfare: The Rise of Hybrid Wars’. U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings Magazine 131, no. 11 (2005): 18–19.

McCuen, John J. ‘Hybrid Wars’. Military Review, no. April (2008): 107–13. http://www.au.af.mil/au/awc/awcgate/milreview/mccuen08marapr.pdf.

Mcculloh, Timothy, and Richard Johnson. ‘Hybrid Warfare’. Jboint Special Operations University. Florida, 2013. https://jsou.libguides.com/ld.php?content_id=2876897.

McWilliams, Sean J. ‘Hybrid War Beyond Lebanon: Lessons from the South African Campaign 1976 to 1989’. U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, 2009.

Monaghan, Andrew. ‘The “War” in Russia’s “Hybrid Warfare”’. Parameters 45, no. 4 (2016): 65–74.

NATO. ‘A “‘comprehensive Approach’” to Crises’. NATO Website, 2018.

———. ‘Keynote Speech by NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg at the Opening of the NATO Transformation Seminar’. NATO Website, 2015. https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/opinions_118435.htm.

———. ‘NATO’s Response to Hybrid Threats’, 2019. https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_156338.htm.

Nemeth, William J. ‘Future War and Chechnya: A Case for Hybrid Warfare’. Naval Postgraduate School, 2002. https://calhoun.nps.edu/bitstream/handle/10945/5865/02Jun_Nemeth.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

Popescu, Nicu. ‘Hybrid Tactics : Russia and the West’, no. October (2015): 2014–15. https://doi.org/10.2815/28861.

Porche III, Isaac R., Christopher Paul, Michael York, Chad C. Serena, Jerry M. Sollinger, Elliot Axelband, Endy Y. Min, and Bruce J. Held. Redefining Information Warfare Boundaries for an Army in a Wireless World. RAND Corporation, 2013.

Raitasalo, Jyri. ‘Hybrid Warfare : Where ’ s the Beef?’ War On The Rocks, 2015, 1–5. http://warontherocks.com/2015/04/hybrid-warfare-wheres-the-beef/.

Rauta, Vladimir. ‘Towards a Typology of Non-State Actors in “Hybrid Warfare”: Proxy, Auxiliary, Surrogate and Affiliated Forces’. Cambridge Review of International Affairs 33, no. 6 (2020): 868–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/09557571.2019.1656600.

Renz, Bettina. ‘Russia and “Hybrid Warfare”’. Contemporary Politics 22, no. 3 (2016): 283–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569775.2016.1201316.

Renz, Bettina, and Hanna Smith. ‘Russia and Hybrid Warfare – Going beyond the Label’. Aleksanteri Papers, 2016. www.helsinki.fi/aleksanteri/english/publications/aleksanteri_papers.html.

Robinson, Linda, Todd C Helmus, Raphael S Cohen, Alireza Nader, Andrew Radin, Madeline Magnuson, and Katya Migacheva. Modern Political Warfare: Current Practices and Possible Responses. RAND Corporation, 2018. https://doi.org/10.7249/RR1772.

Saunders, Paul J. ‘Why America Can’t Stop Russia’s Hybrid Warfare’. The National Interest, June 2015. https://nationalinterest.org/feature/why-america-cant-stop-russias-hybrid-warfare-13166.

Schroefl, Josef, and Stuart J. Kaufman. ‘Hybrid Actors, Tactical Variety: Rethinking Asymmetric and Hybrid War’. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 37, no. 10 (2014): 862–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2014.941435.

Seely, Robert. ‘Defining Contemporary Russian Warfare Beyond the Hybrid Headline’. RUSI Journal 162, no. 1 (2017): 50–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/03071847.2017.1301634.

Seppälä, Tiina. ‘“New Wars“ and Old Strategies: From Traditional Propaganda to Information Warfare and Psychological Operations’. In 23 Conference and General Assembly IAMCR/AIECS/AIERI International Association for Media and Communication Research, Barcelona,. Barcelona, 2002.

Strachan, Hew. The Direction of War: Contemporary Strategy in Historical Perspective. Cambridge University Press, 2013.

Suchkov, Maxim A. ‘Whose Hybrid Warfare? How “the Hybrid Warfare” Concept Shapes Russian Discourse, Military, and Political Practice’. Small Wars and Insurgencies, 2021, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/09592318.2021.1887434.

Taylor, Philip M. Munitions of the Mind. A History of Propaganda from the Ancient World to the Present Era. Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press, 1995.

Tenenbaum, Élie. ‘Hybrid Warfare in the Strategic Spectrum: An Historical Assessment’. In NATO’s Response to Hybrid Threats, edited by Guillaume Lasconjarias and Jeffrey A. Larsen. Rome: NATO Defence College, 2015.

Treverton, G. F., A. Thvedt, A. R. Chen, K. Lee, and M. Mccue. Addressing Hybrid Threats, 2018. https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1219292/FULLTEXT01.pdf.

Tuck, Chris. ‘Hybrid War : The Perfect Enemy’, 2017. https://defenceindepth.co/2017/04/25/hybrid-war-the-perfect-enemy/.

U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff. JP 3-13 Information Operations. U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, 2014. https://fas.org/irp/doddir/dod/jp3_13.pdf.

UK House of Commons Defence Committee. ‘The Comprehensive Approach: The Point of War Is Not Just to Win but to Make a Better Peace’. HC 224, Seventh Report of Session 2009–10, 2010.

United States Government Accountability Office. ‘Hybrid Warfare Report’. Washington, 2010.

US Joint Chiefs of Staff. ‘Joint Publication 3-05 Doctrine for Joint Special Operations’, no. July (2014). https://www.jcs.mil/Portals/36/Documents/Doctrine/pubs/jp3_05.pdf.

Vershbow, Alexander. ‘Remarks by NATO Deputy Secretary General at the SDA Conference: Overhauling Transatlantic Security Thinking- Newswire, June 4, 2014 Wednesday’. States News Service, 2014.

Walker, Robert G. ‘SPEC FI: The United States Marine Corps and Special Operations’. Naval Postgraduate School, 1998. https://calhoun.nps.edu/bitstream/handle/10945/8989/specfiunitedstat00walk.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

Murat Caliskan is a former Turkish military officer. Currently, he works as a cybersecurity analyst and gives lectures at the Université Catholique de Louvain/Belgium. His research interest include Strategic Theory, Grand/Military Strategy, Contemporary Warfare, UN Peacekeeping Operations and Belgium Foreign Policy in the UN Security Council.