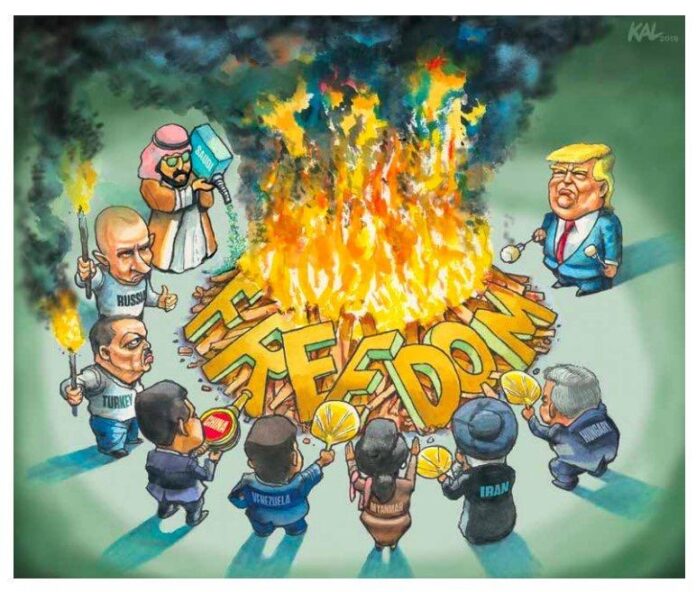

The post-World War II liberal world order has faced major ideological challenges from external actors and has successfully managed to overcome them[2]. Nevertheless, it is currently exhibiting signs of deterioration[3]. Liberal principles[4] and democratic institutions are being pulled apart. Even more than a setback in democracy, we are witnessing a crisis of liberalism[5].

The emerging illiberal democracies are on the rise not only in the countries that have long practiced authoritarianism, such as China and Russia, but also in European nations with a background of liberal democracy [6]. Illiberal leaders and political parties are threatening democracy by targeting liberal judicial oversight, pluralistic political systems, independent media, and open civil society,[7] all of which can bring about the breakdown of the liberal order. Democracy without constitutional liberalism[8] is not merely inadequate but dangerous, bringing with it the erosion of liberty, the abuse of power, ethnic divisions, and even war. [9]

An important part of these challenges comes from illiberal democracies within the international organizations (IOs) that are the linchpins of the liberal world order. Although much has been said about the future of the liberal world order and illiberal democracies[10], there has been scarce discussion on how the recent illiberal trends will affect IOs.

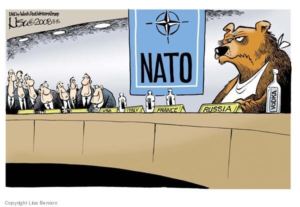

How do international organizations respond when member states disrupt political cohesion and go against the ideals the institutions are built on? What can those organizations do when the contrarian member governments are working to undermine and break the organizations, and the organizations lack ready tools for compliance, punishment, or incentivization?[11]

Organization theory would claim that an organization would try to survive by various means.[12] What would that mean when the point of contention is not policy but rather norms? The scenario above becomes a more convoluted problem when one accounts for the differing approaches major international relations(IR) frameworks take to the IOs: the neorealist focus on power and distrust of IOs’ usefulness and capacity, the liberal institutional view of the benefits of institutional membership, and the constructive argument of identity and norms.

The question becomes even more pertinent to lynchpin organizations like the EU and NATO that carry heavy political and security roles. These organizations hold liberal democratic values at the heart of their existence. Lisbon Treaty and EU Charter of Fundamental Rights list Human Dignity, Freedom, Democracy, Equality, Rule of Law, and Human Rights as core EU values.[13] NATO’s founding document, the Washington Treaty, asserts that the members are “determined to safeguard the freedom, common heritage, and civilization of their peoples, founded on the principles of democracy, individual liberty, and the rule of law.” [14] [15]

These values are a significant part of the glue that has held EU and NATO member states together, and these treaties are not a menu of options from which allies can select some obligations while ignoring others.

There is a noticeable drift from its core values within some member states in liberal institutions. Nowadays, multiple members of democratic alliances are experiencing a transition from democracy to autocracy or even dictatorship, from human rights advocacy to human rights violations championship and overthrowing the rule of law. A democratic alliance must address the authoritarian centralization of executive power, suppression of free press, civil society, and political opposition, and interference with the judiciary whenever these occurrences take place in member states.

For example, in 2019, NATO faced perhaps the most daunting and complex set of challenges in its history, both from within the alliance and beyond its borders.[16] “The challenges confronting NATO in 2019 were numerous and multifaceted. These challenges emerged both from within the alliance and beyond NATO’s borders. Of particular significance was a challenge unprecedented in NATO’s history: the absence of robust American presidential leadership. Urgent action by NATO’s leaders was necessary to address these tests and bridge the widening divisions within the Alliance before it became too late.”

Indeed, NATO has experienced a significant transformation over the past even decades. The frequency and audacity of these changes distinguish NATO from other international institutions.[17] Yet both adaptation and endurance characterize NATO.

However, the rise of authoritarian tendencies that erode democratic values is not entirely new to the Alliance. NATO has seen military dictatorships in the past.[18] While twenty-six of the twenty-nine allies are still rated as “free”, compared with only 45 percent of states worldwide across twenty-five indicators of democracy rated by Freedom House, the downward trend among NATO allies over the past decade is stark.[19] The United States is not immune, with its Freedom House rating declining in 2018 due to “Russian interference in the 2016 election, violations of basic ethical standards by the new administration and a reduction in government transparency and the gradual decline of American enthusiasm for the IOs or International treaties from its peak in the early post–World War II era.

All against these, the Treaty is not a selection of choices from which allies can pick some obligations while disregarding others, and the Treaty has no provision for policing members that drift from common political values, unlike the European Union Treaty’s[20] Chapter 7 that has been invoked recently toward several EU member states with some success.

What can the EU and NATO do to counter the democratic backsliding within its ranks? Can “strategic necessity” trump “values”?[21] It is no overstatement that the EU and NATO need the institutional tools and actors to avoid “extreme confrontation” or “excessive accommodation” to successfully transform itself, just as it has done in the wake of the critical juncture at the collapse of the Cold War order.

This study will consider “the emerging illiberal members of IOs” as the most severe challenge[22] to the IOs and the liberal world order. It will focus on how IOs respond to those illiberal members to maintain their existence and identity and how this response will affect international relations and the liberal world order.

In light of the discussion above, the questions can be succinctly identified as:

“How do IOs react to fundamental changes in their wayward members, which diametrically oppose the ideological standings of the organization for the short term and set preventive measures for the long term? In particular, how will organizations like the EU and NATO react to the wave of illiberal democracies forming within, to remain relevant for today, and prepare for the future?”

Role of International Organizations in major international relations theoretical frameworks

The main international relations frameworks have differing approaches on the role of institutions, which stems from their main tenets. Neorealist tradition has approached the issue of IOs with reluctance, simply because neorealists believe that there is not much room for cooperation in the international order as international politics is already at the “Pareto frontier”[23]. To further divide neorealism into offensive and defensive neorealism yields two differing takes within the framework. The offensive realists fundamentally believe that mutual security cannot be gained, and states will make a move to maximize power when opportunities present themselves. As a result, IOs are seen as temporary frameworks that exist as long as all participants believe there is no suitable opportunity for revisionist moves. The prisoner’s dilemma approach infused with offensive realist thinking does not leave much space for institutions as long-lasting, powerful actors. The defensive realist school generally accepts that there is suboptimal cooperation in international relations; thus, theoretically, an opportunity exists for IOs to be facilitators of cooperation.

However, factors such as the lack of faith in the actors to agree on common interests, biases, mistrust, fear of exploitation, and the cost of cheating constitute barriers to cooperation. Robert Jervis analyzes the factors that would lead to increased cooperation and argues that perceived diagnosis of the situation and other objectives are key factors for defensive realists[24]. Thus, for neorealists, the IOs are established and maintained as long as the states involved are seeking the same goals that the establishment and continuation of IOs will help them achieve.

Unlike the realist perspective, the neoliberal framework gives a heavy premium to institutions. Neoliberalism, at its core, argues that there is more potential for cooperation in international relations, and the International Organizations are a reflection of that reality. For authors like John Ikenberry, the persistence of the post-WW2 Western order cannot be explained with power-centric theories such as balance of power or hegemony[25]. Instead, international organizations and the accompanying strategies have rendered the world order more acceptable to other rising powers such as Japan and. Europe. The mechanism on how IOs achieve more stable wider structures of politics and society lies in two core logics:

Firstly, the IOs reduce the risk of participation by establishing a constitution-like structure and practices which results in reduced returns for power. The constitutional bargain theory claims that the IOs benefit both the winners and losers following a conflict. The winner locks in a favorable arrangement that will continue to function even after winners are beyond the zenith of their power. Also, the winner benefits the IOs through reduced implementation cost of the order as others are willing participants of the system. The losers also benefit the IOs as they would suffer more under a power-based post-conflict settlement. Besides, there is a degree of security within the rule-based institutional order that would protect the weak from the threat of domination and abandonment.

Secondly, the institutions have an “increasing returns” character which means that any contender to the established order would face increasing difficulty in time to challenge the established beliefs, norms, and the actors. Once the organizations are established, they become more deeply rooted in the system and develop vested interests and stakes in the system that steadily grow over time. As a result, it becomes increasingly difficult to overcome the sunk cost aspects of participating in the existing organization and thus presents higher start-up costs for any contender.

The constructivist framework provides some assumptions that shift the emphasis from power. Constructivists view the international structure as a social structure with norms, rules, and laws. Also, since states are not regarded as the only major actors, IOs are valid agents of the international structure with their own identities, interests, norms, and rules. Key concepts within the constructivist framework, such as the logic of appropriateness, where norms and rules are associated with particular identities and particular situations, can provide ground for the establishment and continuation of the IOs. It is possible to argue that focusing on shared ideas rather than material forces and regarding identities and interests as constructed rather than given concepts provide firm ground for explaining the existence and purpose[26]. However, the most important contribution of constructivism to understanding the IOs could be in explaining the change. Constructivists believe that identity, interests, and norms are not constant and change with shared ideas; thus, the changes within the IOs and changing attitudes towards the IOs find an explanation through the constructivist framework.

The Theory of International Organizations

When studying the IOs, there are two main perspectives: The Regime Approach and The Institutional Approach. The two perspectives differ mainly on who they treat as the main actor. The regime approach regards the states as the main actor, while the institutional approach regards the IOs themselves as the main actor. The institutional approach was popular in the post-WW2 setting, but the regime approach took hold in the 1980s and 1990s. Recently, the institutional approach has made a comeback in the post-war era.[27]

The main question of who the actor is results in fundamentally different questions in an analysis.

Institutionalists are interested in what happens within the organizations, while regime analysis is more focused on the behavior of states and the rules that the organizations adopt. The regime approach’s critique of the institutional approach rests on the claim that the institutional approach fails to analyze the larger picture and contribute to understanding the behavior patterns in international relations. However, the institutional approach has a better track record of explaining the commitments of IOs to self-preserve and grow. The evolution of the IMF and EU cannot be explained within the regime framework.

It should be noted that there is also a third school of thought that focuses on principles and norms rather than actors. The reflectivists are more interested in questions regarding what ideas and norms drive the IOs.

The concept of power, particularly the power relationship between the states and the IOs, frequently comes up in theoretical discussions[28], [29]. It is a truism to state that states and IOs are asymmetrical when it comes to the source and manifestation of power. IOs are created by states and face termination from the same states that established them. Besides, IOs depend on states for their day-to-day functioning, especially through funding. Most importantly, IOs lack the most pervasive aspect of power in international relations: military power. Institutional Liberalists argue that despite these shortcomings, IOs have acquired sources of power. Some IOs, such as the International Court of Justice and Dispute Settlement Mechanism within the World Trade Organizations, have the power to adjudicate conflicts.

The Realist response to this argument is that the source of power in such judicial roles is the backing of States since IOs lack the enforcement capability, and thus, IOs do not have power per se. However, in most of the cases, the enforcement is hardly carried through the use of force. The states comply with IO rulings for various reasons. States find their benefit to continue being good-standing participants of the international system and shy away from attitudes that would be perceived otherwise. Thus, the argument is that IOs have a moral authority that empowers them. IOs make use of this power through various methods, including name and shame methods. Such an approach is widely used by scholars, especially in the field of Human Rights.[30]

Lastly, the concept of “conditionality” becomes an important part of spoiler discussions. The “conditionality” that NATO and especially the EU eventually created for its aspiring members – including specific targets and annual assessment reports – became a well-known policy practice. Conditionality can be defined as an actor linking “perceived benefits to another state, such as financial assistance, trade concessions, co-operation agreements, political contacts or even membership, to the fulfilment of certain conditions.”[31] Fawn makes a distinction between external conditionality, which can be viewed as the material and procedural requirements presented by an IO, while internal conditionality deals more with values and norms.[32] The recalcitrant members face the danger of internal conditionality being manifested by other members when they go against the accepted rules and norms of the organization.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the emergence of illiberal democracies within international organizations poses a significant challenge to the liberal world order and the foundational principles upon which these organizations were built. As outlined in this study, the response of international organizations, particularly lynchpin entities like the EU and NATO, to such fundamental shifts within their member states is crucial for their continued relevance and effectiveness.

The theoretical frameworks of international relations offer various perspectives on how international organizations function and interact with their member states. From neorealism’s skepticism towards the efficacy of institutions to neoliberalism’s emphasis on their stabilizing role and constructivism’s focus on norms and identities, each framework provides insights into the dynamics at play.

Moreover, the analysis of international organizations through the lens of regime theory and institutional theory highlights the complexities of organizational behavior and the challenges in balancing state interests with institutional objectives. The concept of power, both within and outside of international organizations, underscores the asymmetrical nature of their relationships with member states and the mechanisms through which they exert influence.

In addressing the rise of illiberal democracies within their ranks, international organizations must balance strategic necessity and adherence to core values. While the temptation to prioritize short-term geopolitical concerns may exist, compromising on fundamental principles risks undermining the legitimacy and effectiveness of these organizations in the long run.

One potential avenue for international organizations to counter democratic backsliding is through the strategic application of conditionality, both internally and externally. By linking benefits and privileges to the fulfillment of democratic norms and values, organizations like the EU and NATO can incentivize member states to uphold liberal democratic principles while also demonstrating a commitment to their founding ideals.

In the face of evolving global challenges and internal disruptions, international organizations must remain adaptive and resilient. They must reaffirm their commitment to liberal democratic values while effectively addressing the concerns and grievances of their member states. Only through proactive engagement and principled leadership can these organizations navigate the complexities of the contemporary international landscape and uphold the liberal world order for future generations.

See more articles in Security and Defense Policy Studies page.

EndNotes:

[1] Deputy Director of NAVI Research Institute- Research Fellow

[2] Richard Haass, “How a World Order Ends and What Comes in Its Wake”, December 11, 2018

https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/2018-12-11/how-world-order-ends , Accessed 07.03.2019

[3] Rodger Baker, “Challenging the Inevitability of the Liberal World Order”, Stratfor, Jul 26, 2018

https://worldview.stratfor.com/article/challenging-inevitability-liberal-world-order?utm_source=LinkedIn&utm_medium=social&utm_campaign=article, Accessed 07.03.2019

[4] Liberal principles—political ideas that espouse the importance of individual liberties, minority rights, and the separation of power across levers of government

[5] Alina Polyakova, et alii, “The Anatomy of Illiberal States: Assessing and responding to Democratic Decline in Turkey and Central Europa”, Washington, DC, Foreign Policy at Brookings, February 2019

[6] Richard Haass, “How a World Order Ends and What Comes in Its Wake”, December 11, 2018

https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/2018-12-11/how-world-order-ends , Accessed 07.03.2019

[7] Alina Polyakova, et alii, “The Anatomy of Illiberal States: Assessing and responding to Democratic Decline in Turkey and Central Europa”, Washington, DC, Foreign Policy at Brookings, February 2019

[8] Fareed Zakaria, “The Rise of Illiberal Democracy”, Foreign Affairs, Nov/Dec 1997; 76,6, for the liberal democracy, the constitutional liberalism, illiberal democracy and liberal autocracy

[9] Fareed Zakaria, “The Rise of Illiberal Democracy”, Foreign Affairs, Nov/Dec 1997; 76,6, pp. 43

[10] G. John Ikenberry, “The Future of the Liberal World Order,” Foreign Affairs, May/June 2011, 56-68. Charles A. Kupchan, “The Normative Foundations of Hegemony and the Coming Challenge to Pax Americana”, Security Studies 23:2,2014, pp. 219-257.

[11] Rick Fawn, “International_Organizations and Internal Conditionality”, Palgrave Macmilan, NewYork, 2013, pp.1

[12] It would also be interesting to see if the Allison’s Organizational Behavior model applies to international organizations or whether organizational theory provides insight into the conflicts in the international organizations. Graham Allison and Philip Zelikow, “Essence of Decision”, 2nd ed., New York, NY: Longman, 1999,

[13] “Goals and Values of EU”. The EU in Brief. European Union, https://europa.eu/european-union/about-eu/eu-in-brief_en Accessed 22.09.2019

[14] The North Atlantic Treaty, NATO, https://www.nato.int/cps/ie/natohq/official_texts_17120.htm , Accessed 24.02.2019

[15] NATO Strategic Concept -2010, Core Tasks and Principles

[16] Ambassador Douglas Lute Ambassador Nicholas Burns, “NATO at Seventy an Alliance in Crisis”, Harvard Kennedy School’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, February 2019

[17] Seth A. Jonston, “ How NATO Adapts ” John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore ,2017, page1

[18] NATO is experienced with dealing with junta regimes like the Franco Spain, Salazar Portugal, or post-coup regimes in Greece and Turkey. But the security environment changed significantly since the end of the Cold War.

[19] Especially in Central Europe but not exclusively, there are setbacks in the media, the judiciary and the functioning of national democratic institutions. The rate at which democracy is declining in Poland, Hungary and Turkey is particularly alarming. In 2017 and 2018, these three states’ scores represented some of the largest one-year declines in political rights and civil liberties of all 195 countries ranked by Freedom House. Poland—with the largest category declines in the forty-year history of the survey—is close to leaving the “consolidated democracy” category. Hungary is no longer rated a consolidated democracy. Turkey, whose decline in freedom over the last ten years represents the largest of any country in the world, crossed the threshold from “free” to “not free. ”See “Freedom in the World 2018” , Washington, DC: Freedom House, 2018, https://freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/FH_NationsInTransit_Web_PDF_FINAL_2018_03_16.pdf., Accessed 20.02.2019

[20] Treaty of Lisbon amending the Treaty on European Union and the Treaty establishing the European Community, signed at Lisbon, 13 December 2007 http://data.europa.eu/eli/treaty/lis/sign

[21] Sven Biscop, “The Dangerous Geopolitics of Populism, and What NATO and the EU Can Do About It”, EGMONT Institute for International Relations Security policy Brief, No. 97, May 2018

[22] Celeste A. Wallander, “NATO’s Enemies Within: How Democratic Decline Could Destroy the Alliance”, ESSAY July/August 2018 Issue, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/2018-06-14/natos-enemies-within

[23] Stephen D. Krasner, “Global Communication and National Power: Life on the Pareto Frontier,” World Politics, Vol. 43, No. 3 (April 1991), pp. 336–366.

[24] Robert Jervis. “Cooperation Under the Security Dilemma”. World Politics. Vol. 30, No. 2 (Jan., 1978), pp. 167-214

[25]John Ikenberry. “Institutions, Strategic Restraint, and the Persistence of American Postwar Order”. International Security, Vol. 23, No. 3 (Winter, 1998-1999), pp. 43-78 Published by: The MIT Press

[26] Alexander Wendt presents tow basic tenets of constructivism as : “The structures of human association are determined primarily by shared ideas rather than material forces, and that the identities and interests of purposive actors are constructed by these shared ideas rather than given by nature” Alexander Wendt, Social Theory of International Politics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999),pp.1

[27] J. Samuel Burkin, “International Organizations: Theories and Institutions” Palgrave Macmilan, NewYork, 2006, pp. 138,

[28] Ibid, pp. 138,

[29] Michael N. Barnett and Martha Finnemore. The Politics, Power, and Pathologies of International Organizations International Organization Vol. 53, No. 4 (Autumn, 1999), pp. 699-732

[30] See scholars as Franklin J.C. “Human Rights Naming and Shaming: International and Domestic Processes” (2015) s. In: Friman H.R. (eds) The Politics of Leverage in International Relations. Palgrave Studies in International Relations Series. Palgrave Macmillan, London.

[31] Fraser Cameron, “An Introduction to European Foreign Policy”, Abingdon, Routledge, 2007, pp. 184.

[32] Rick Fawn, “International Organizations and Internal Conditionality”, Palgrave Macmilan, NewYork, First published 2013, pp. 1-19

As a graduate of the U.S. Army War College and a former senior civil servant, Mr. Umit Kurt is dedicated to advancing the field of international relations as a Ph.D. researcher at UCLouvain in international relations in Belgium.

His research delves into the dynamics of International Institutions with their diverse members, the ethics of reconciliation, the complexities of migration, and the overarching governance of digital ecosystems.

With a career that spans over two decades, he has been at the forefront of leading and contributing to task forces in various capacities, including NATO Peace Operations and strategic NATO Headquarters.

Mr Kurt’s professional journey has been enriched by a Master of Business Administration. His expertise in Global Governance for Digital Ecosystems was honed through a consultancy role at PA Europe-Belgium, a prominent multinational public affairs firm.